Introduction

More than 60% of oil production and 40% of natural gas production in the world are from carbonate rocks, so carbonate rocks are major oil and gas reservoirs[1,2,3] with huge potential for exploration and development. Compared with clastic reservoirs, carbonate reservoirs often have undergone more complex sedimentation, diagenesis and reformations by tectonic movements, so they have commonly multi-scale and multi-type of pores, vugs, cavities, fractures and other reservoir spaces in various combination patterns[4,5], intricate pore-throat structures, and strong heterogeneity. The complicated pore-throat structure of carbonate reservoirs has complex porosity-permeability relationship[6-9] and the phenomena of high porosity and low permeability. Similar porosities corresponding to permeabilities with different orders of magnitude are common[5, 10-12]. The complicated pore-throat structure has brought challenges to the determination of porosity-permeability relationship of reservoirs, evaluation of reservoir storage and production capacity[12,13] and reservoir protection[14], which severely hinders the comprehensive evaluation and efficient development of carbonate reservoirs. In-depth systematic and quantitative research on pore-throat structures is of great significance for the exploration and development of carbonate oil and gas fields.

Previous studies on pore-throat structures of carbonate rocks mainly focused on the characteristics of pore-throats in different types (mainly pore type reservoir, few pore-cavity and pore-cavity-fracture reservoir) and different lithologies (primarily limestone and few dolomite) of carbonate reservoirs[5,12-13,15-19], controlling factors of pore-throat structure difference, and the influences of pore-throat structure on porosity-permeability relationship of reservoirs through high pressure mercury injection, digital image analysis and fractal dimension methods[5,8,10-11,20-25]. The results of these studies have developed the study of pore-throat structures of carbonate reservoirs, especially the studies on pore-throat structures of pore-type carbonate reservoir dominated by limestone. But for the pore-throat structure of complex carbonate rocks made up of mainly dolomite and some limestone and transitional lithology that contain pores, cavities, and fractures, three problems still remain to be addressed: (1) Lack of a set of classification, description and quantitative characterization approaches for the pore-throat structure of this sort of carbonate rocks. (2) The main factors controlling pore-throat structure differences of this type of carbonate rocks have yet to be revealed. (3) Complex carbonate rocks developed reservoirs with various origins, but studies on the pore-throat structure and the influences of pore-throat structure on porosity-permeability relationship of different reservoirs are scarce.

In this study, taking the Carboniferous carbonate reservoirs in the North Truva Oilfield on the eastern edge of the Pre- Caspian Basin as examples, by combining test and analysis data of cores from 24 coring wells, we performed the following studies on the four types of carbonate reservoirs of pore-cavity-fracture, pore-cavity, pore-fracture and pore types on the basis of previous researches: (1) analysis of petrology and reservoir spaces based on thin sections and scanning electron microscope observations; (2) systematic and quantitative study on pore-throat structure based on analysis of conventional petrophysical properties, high-pressure mercury intrusion (HPMI) and various geochemical testings; (3) classification, description and quantitative characterization methods for the microscopic pore-throat structure; (4) main controlling factors of pore-throat structure differences and influences of pore-throat structure on the porosity and permeability relationship of various reservoirs. We hope that the researches and consequent understandings can provide effective guidance for classification and evaluation of complex carbonate reservoirs and establishment of accurate poro-perm relationships, and optimization of development mode, so pertinent strategies to tap remaining oil potential can be worked out to enhance ultimate recovery of oil and gas fields.

1. Research background

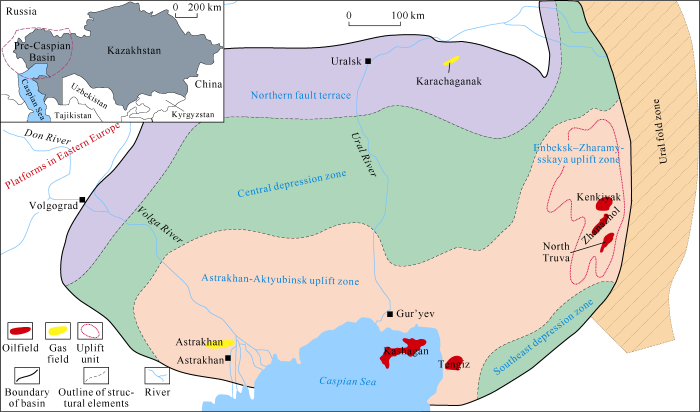

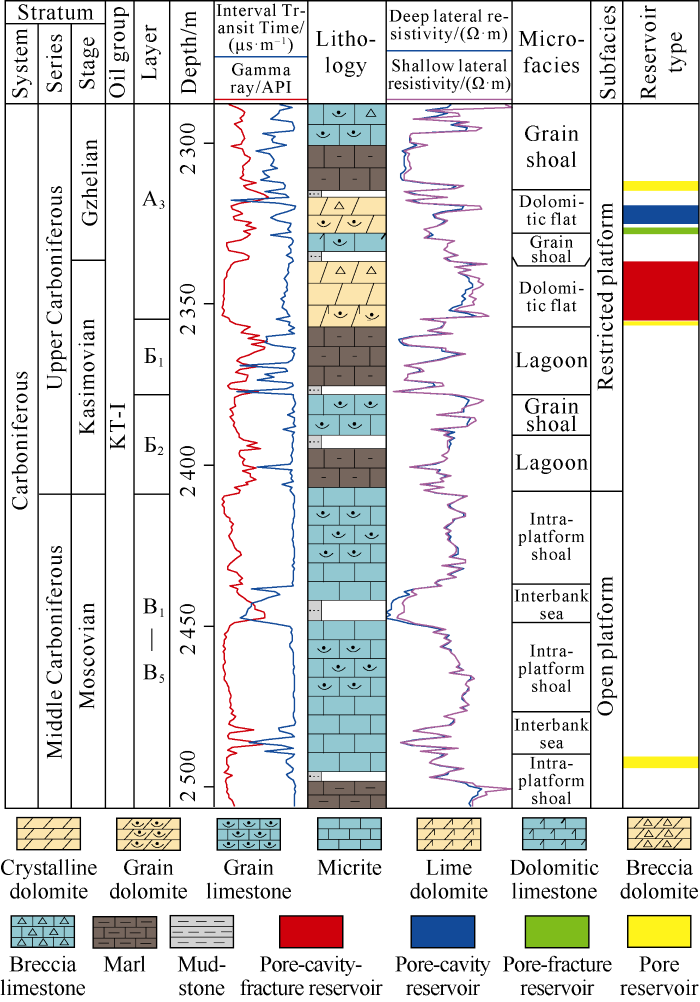

The Pre-Caspian Basin is one of the world’s major petroliferous basins, characterized by fast subsidence rate and large sediment thickness[26]. So far, a series of large and giant carbonate oil and gas fields such as Astrakhan, Tengiz and Kashagan, Zhanazhol, Kenkiyak and North Truva, have been discovered in the Permian pre-salt formations of this basin[27,28] (Fig. 1). The North Truva Oilfield is located in the Enbeksk-Zharamysskaya uplift zone in the east part of the basin (Fig. 1). The Carboniferous consists of carbonate platform sediments of shallow sea facies, and includes two sets of oil-bearing layers, KT-I layer and KT-II layer, from top to bottom respectively. The KT-I layer consists of 10 sub-layers, А1-А3, Б1-Б2, and В1-В5, and develops primarily sediments of restricted platform and open platform facies, and microfacies such as lagoon, dolomitic flat, grain shoal, intra-platform shoal, interbank sea, etc.[5, 26](Fig. 2). The eastern margin of the basin is a northeast-southwest faulted anticline, where, influenced by the Hercynian tectonic movement in the Late Carboniferous, the carbonate formation at the top of the KT-I layer uplifted overall and suffered regional exposure and denudation, so A1 and A2 layers are missing in some wells.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Regional structural map of Pre-Caspian Basin.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Composite stratigraphic column of Carboniferous KT-I layer in the North Truva Oilfield.

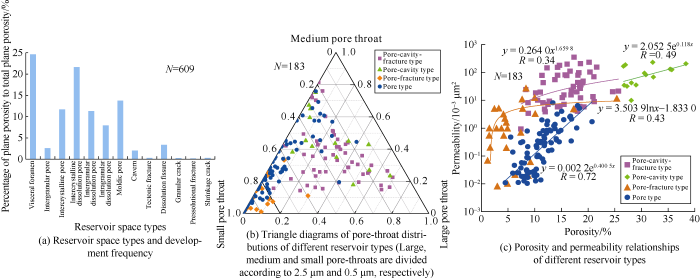

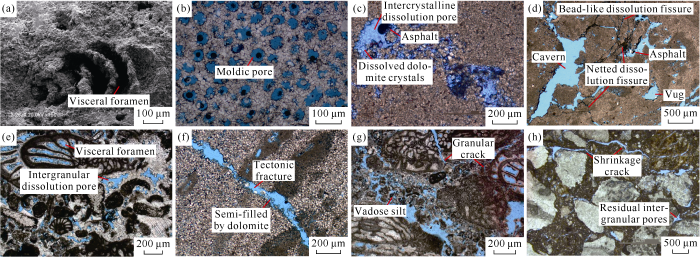

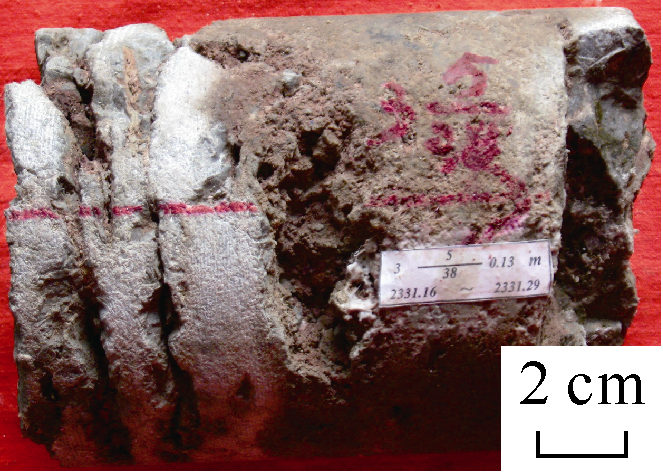

The KT-I layer in the study area is more complicated in lithology, mainly composed of crystalline dolomite, grain dolomite, grain limestone, karst breccia, dolomitic limestone, lime dolomite and argillaceous limestones (Fig. 2). It contains various types of reservoir spaces, intercrystalline (dissolution) pore and visceral foramen, secondarily intergranular (dissolution) pore and moldic pore, and a small amount of other types of pores (Fig. 3a). Vugs, caverns and fractures are also well developed in this layer, and the fractures are largely dissolution ones (Fig. 3a). The types of throats include pore-reducing throat, lamellar throat, tube bundle throat and network throat (Table 1).

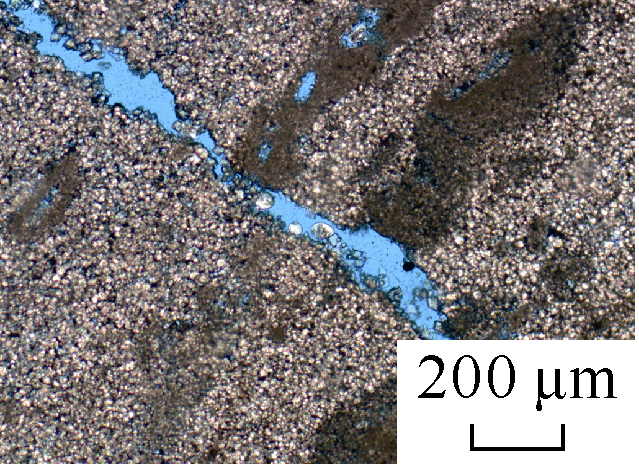

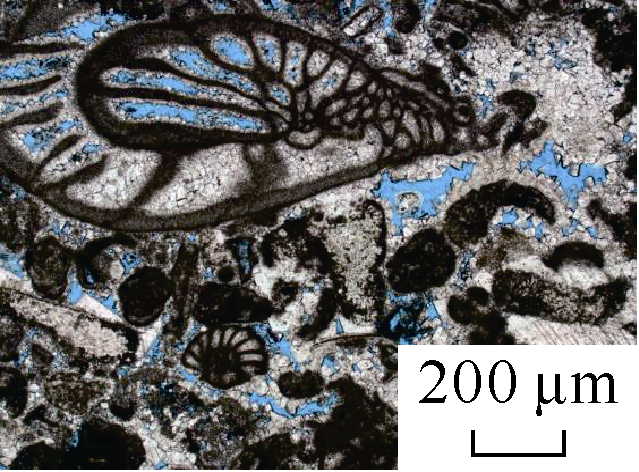

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Reservoir space types, pore-throat distributions and porosity-permeability relationships of the KT-I layer reservoirs in the Carboniferous of the North Truva Oilfield. N—number of samples.

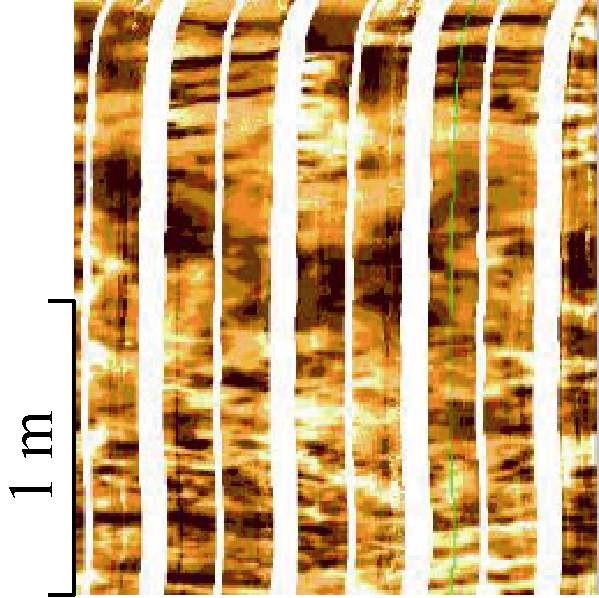

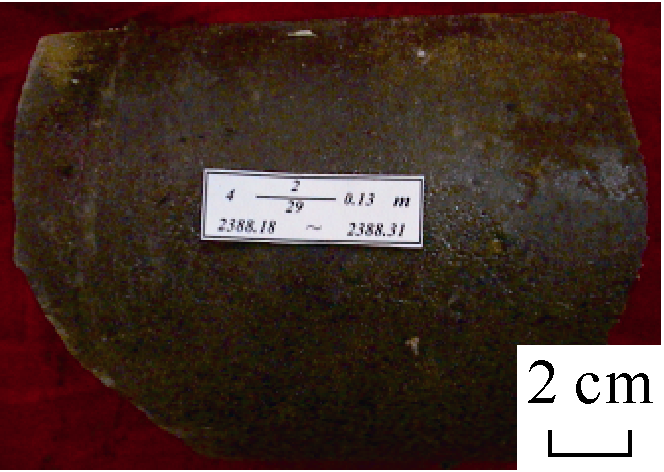

Table 1 Characteristics of different types of reservoirs in the Carboniferous KT-I layer, North Truva Oilfield.

| Reservoir type | Main lithology | Core | FMI | Thin section | Poro- sity/% | Permea- bility/ 10-3 μm2 | Average pore throat radius/μm | Sorting coeffi- cient | Efficiency of mercury withdrawal/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

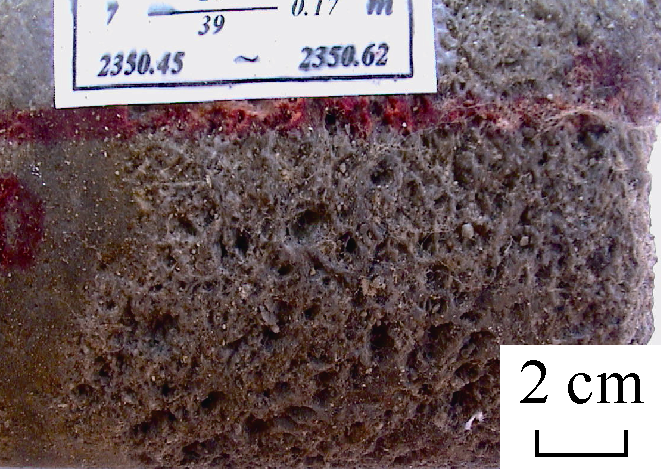

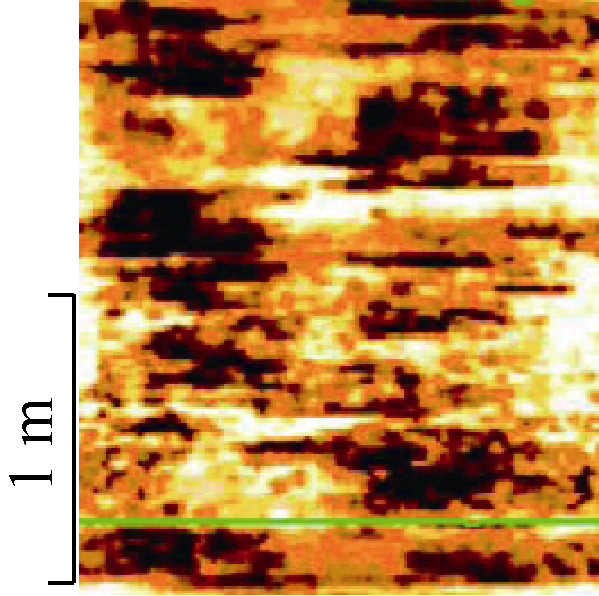

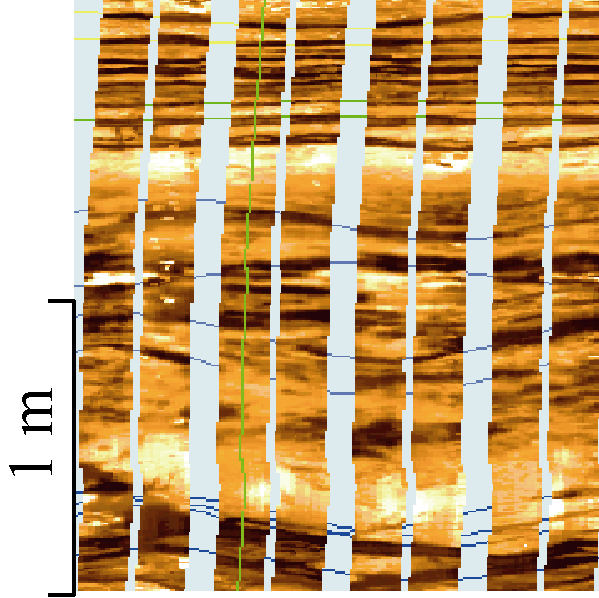

| Pore-cavity-fracture type | Silty dolomite, silty-micritic dolomite, micritic dolomite and grain dolomite |  5555, 2 331.16 m |  CT-11, 2 341-2 343 m |  CT-4, 2 341.66 m | 7.40- 25.70 (16) | 0.93- 349.00 (54.6) | 0.56- 11.10 (3.27) | 1.72-3.87 (2.53) | 15.50- 74.10 (37.4) |

| Pore-cavity type | Micrite, silty-micritic dolomite and biologic grain limestone |  CT-22, 2 350.45 m |  CT-65, 2 727-2 729 m |  CT-59, 2 423 m | 26.70- 38.40 (30.6) | 9.94- 230.00 (103.2) | 0.68-6.03 (2.78) | 1.59-2.54 (2.06) | 30.30- 66.60 (52.7) |

| Pore-fracture type | Grain limestone, silty dolomite, karst breccia limestone |  CT-10, 2 350.58 m |  CT-10, 2 346-2 348 m |  5555, 2 345.72 m | 1.18- 25.40 (6.34) | 0.01- 27.60 (3.71) | 0.01- 10.20 (1.31) | 0.96-3.86 (1.85) | 11.20- 62.50 (29.6) |

| Pore type | Foraminiferal limestone, calcarenite, micritic dolomite |  CT-10, 2 388.19 m |  CT-1, 2 366-2 368 m |  CT-22, 2 299.93 m | 4.50- 20.80 (11.1) | 0.01-8.16 (0.74) | 0.03- 10.30 (2.17) | 1.09-3.34 (1.96) | 2.35- 57.70 (27.6) |

Note: The values in bracket are average values.

According to the type, combination pattern and proportion of the reservoir space, the reservoirs in the study area are divided into four types: pore-cavity-fracture reservoir, pore-cavity reservoir, pore-fracture reservoir and pore reservoir (Table 1), and the quantitative information of reservoir spaces was counted based on the corresponding thin sections of mercury intrusion plugs to identify the reservoir types of mercury intrusion samples. In general, the pore-cavity-fracture and pore-cavity reservoirs are dominated by dolomite and have large to medium pore-throats. The pore reservoirs are mainly limestone with medium to small pore-throats. The pore-fracture reservoirs include various rocks and contain mostly small pore-throats (Table 1, Fig. 3b). However, as carbonate reservoirs are controlled by compound reformations of sedimentation, diagenesis and tectonism, they have various types of reservoir spaces and diverse combination patterns of pore-throats, and each type of carbonate reservoir has very strong heterogeneity microscopically. Therefore, after subdi-vision of the carbonate reservoirs in the study area, although the porosity and permeability data points of various types of reservoirs fall in different ranges, they are in overall discrete distribution, and show poor correlation (Fig. 3c).

2. Classification and characterization for pore-throat structure

As permeability is mainly controlled by degree of pore development (i.e. porosity) and pore-throat structure[9, 29], and reservoir classification primarily considers the development types and combination patterns of reservoir spaces, but doesn’t take the differences in pore-throat structure into account, the same type of reservoir still has poor correlation between porosity and permeability. To improve the calculation accuracy of permeability, it is necessary to do in-depth analysis on the classification and characterization of pore-throat structure.

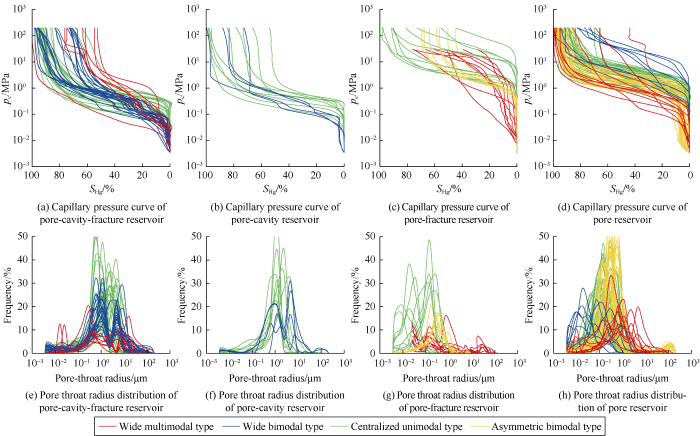

2.1. Classification of pore-throat structure

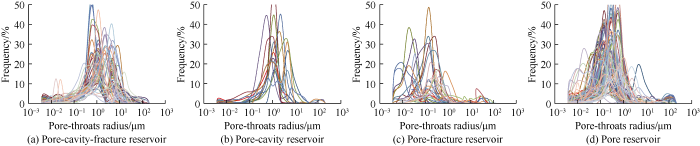

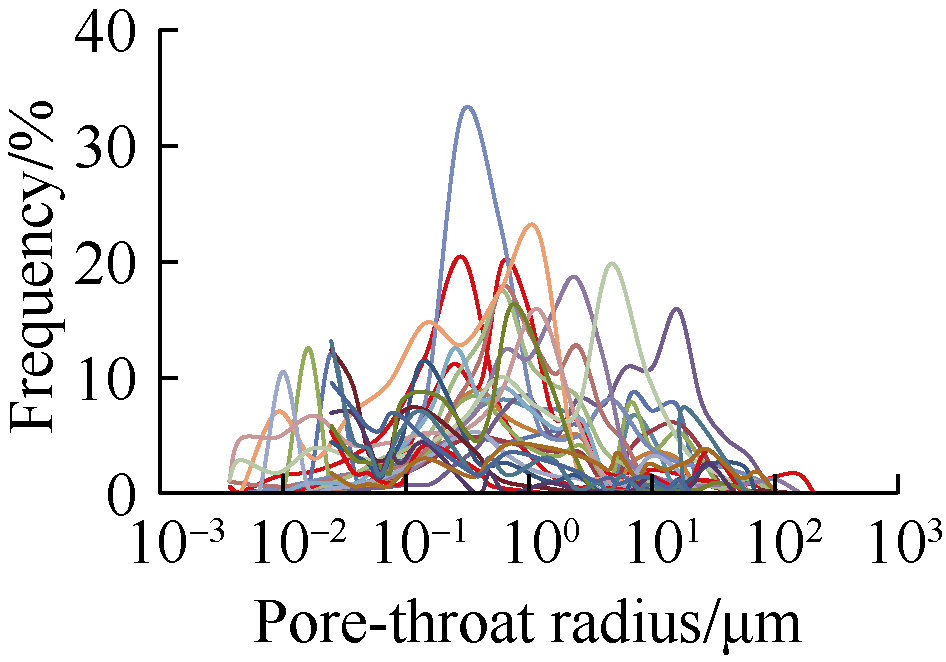

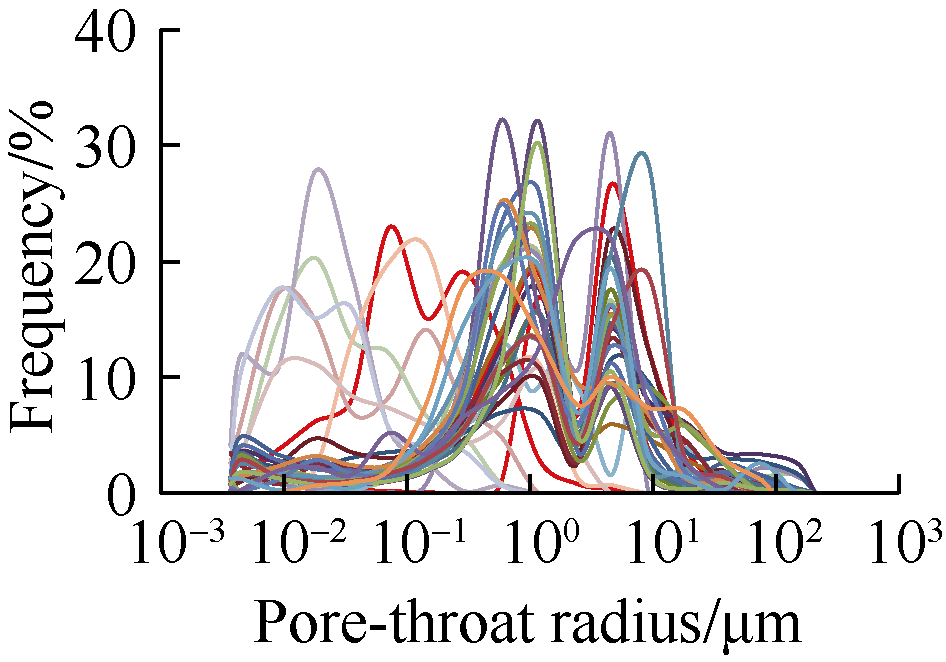

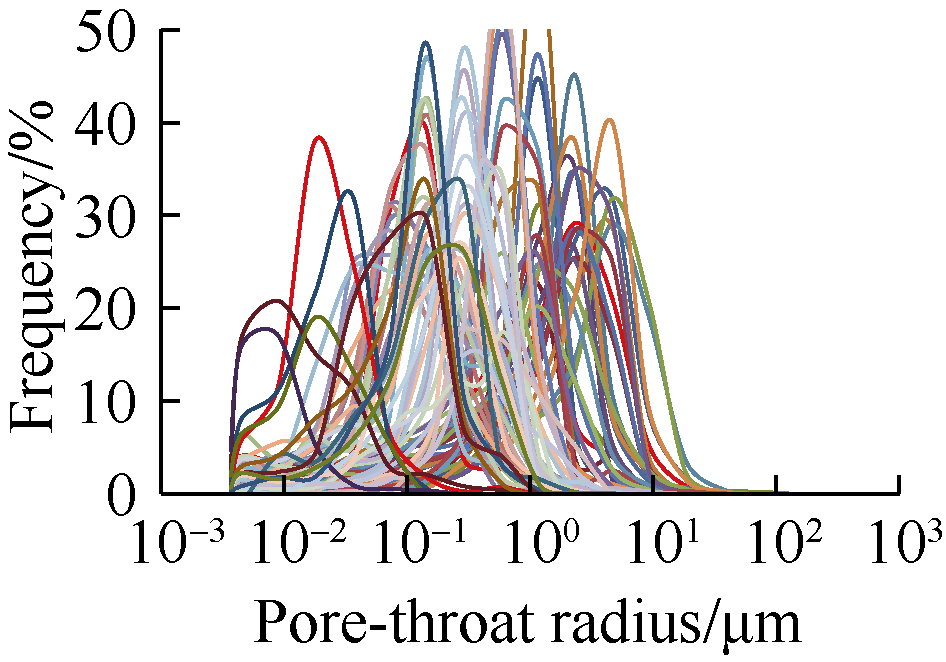

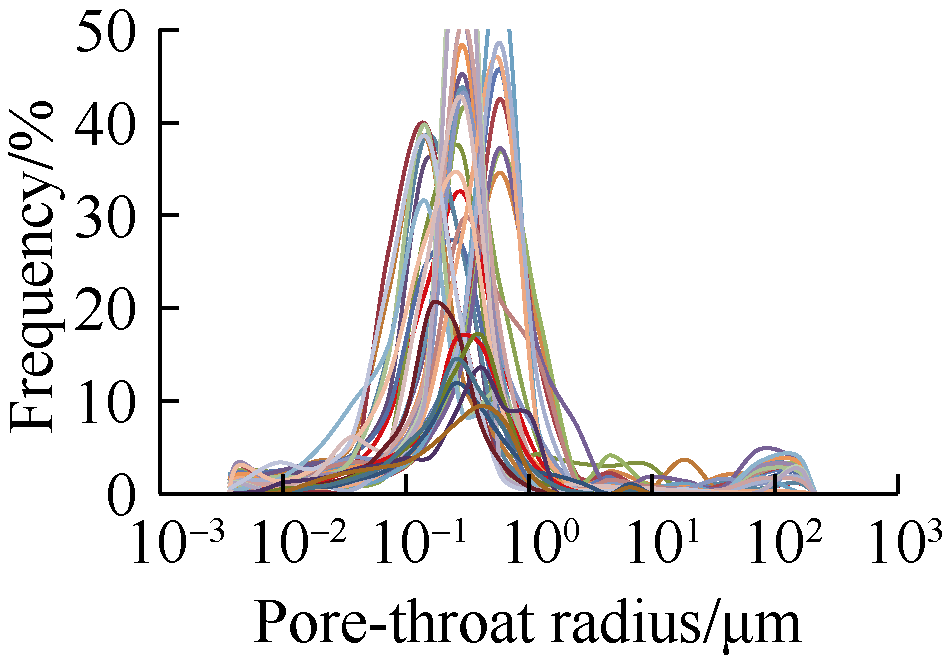

Through in-depth analysis of mercury intrusion data of 4 types of reservoirs in the Carboniferous KT-I layer of the North Truva Oilfield, it is found that each type of reservoir shows various patterns of pore-throat distribution (Fig. 4). The pore-throat structures in the study area can be divided into four types according to the features of frequency distribution curve of pore-throat radius, wide multimodal, wide bimodal, centralized unimodal and asymmetric bimodal types (Table 2).

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Distribution of pore-throat radii in different types of reservoirs of the Carboniferous KT-I layer in North Truva Oilfield.

Table 2 Types of pore-throat structures of Carboniferous KT-I layer in North Truva Oilfield.

| Pore-throat structure type | Frequency distribution curve of pore-throat radii | Average pore-throat radius/μm | Sorting coefficient | Efficiency of mercury withdrawal/% | Porosity/% | Permeability/ 10-3 μm2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wide multi- modal type |  | 0.30-10.92 (3.42) | 1.58-3.86 (2.61) | 16.4-62.5 (39.9) | 1.18-25.40 (11.98) | 0.07-198.90 (27.90) |

| Wide bimodal type |  | 0.03-11.10 (3.52) | 1.41-3.87 (2.62) | 6.3-59.1 (33.7) | 4.50-35.70 (17.50) | 0.01-209.00 (48.70) |

| Centralized unimodal type |  | 0.01-4.65 (0.90) | 0.96-2.59 (1.75) | 2.4-74.1 (33.0) | 2.44-38.36 (13.30) | 0.01-349.00 (26.70) |

| Asymmetric bimodal type |  | 0.25-10.30 (4.10) | 1.14-3.12 (2.17) | 8.4-57.7 (27.4) | 3.00-16.90 (10.90) | 0.01-2.68 (0.56) |

Note: The values in brackets represent average value; different color lines represent data of different samples.

The wide multimodal type has 3-4 peaks of pore-throat radius frequency, strong irregularity of the curve shape, wide frequency band of peak distribution, and an average pore- throat radius of 3.42 μm. The wide bimodal type has two peaks of pore-throat radius frequency, small difference between main peak and secondary peak frequency, strong irregularity of the curve shape, wide frequency band of peak distribution, and an average pore-throat radius of 3.52 μm. The centralized unimodal type has one peak of pore-throat radius frequency, regular shape of curve, narrow frequency band of peak distribution, and an average pore-throat radius of 0.9 μm. The asymmetric bimodal type has two peaks of pore- throat radius frequency with significant difference between the main peak and secondary peak unlike the wide bimodal type. The main peak with high dominant value has corre-sponding pore-throat radius of more than 0.14 μm and average pore-throat radius of 0.32 μm, while the secondary peak with very low value has a corresponding average pore-throat radius of 98.78 μm. The curve of this type presents weak irregularity and wide frequency band of peak distribution.

Among the four types of pore-throat structures, the wide multimodal and wide bimodal types have larger pore-throats radius, poorer pore-throat sorting, and better pore-throat connectivity and reservoir physical property. Meanwhile, the wide bimodal type has better physical properties than wide multimodal type, indicating that the wide multimodal type has strongly heterogeneous pore-throat structures, large span of pore-throat sizes, big difference of distribution frequencies of various sizes of pore-throats, and smaller proportion of large pore-throats above 2.5 μm than the wide bimodal type (Table 2). Therefore, even though with large pore-throats, the reservoir with this type of pore-throat structure has very uneven configuration of pore-throats of different sizes, and thus poorer physical property. The centralized unimodal type has a smaller pore-throat radius, better pore-throat sorting, better pore-throat connectivity and physical property; whereas the asymmetric bimodal type has a larger pore-throat radius, average pore-throat sorting, poorer pore-throat connectivity and physical property, and is the worst among the four types of pore-throat structures (Table 2).

2.2. Quantitative criteria for pore-throat structure identification

Quantitative parameters of different pore-throat structures have different degrees of overlap in characterizing pore-throat structures, so the pore-throat structures cannot be distinguished and characterized by a single parameter (Table 2). In this study, the multi-information fusion technology was adopted, and quantitative parameters (R5, Skp, Dr and Vma) sensitive to the four types of pore-throat structures were selected as input parameters by the cross-plot method. R5 is similar to displacement pressure, and can represent the size of pore-throat mercury enters first. The larger the value of R5, the better the reservoir physical property is. Skp is a measure of the asymmetry of frequency distribution curve of pore-throat sizes, and reflects the relative position of the pore-throat mode. Coarse skewness means that the mode of pore-throat size is close to the coarse pore-throats, which indicates better reservoir physical property, conversely, fine skewness represents poor physical property. Dr represents the homogeneity of pore-throat sizes, equivalent to variation coefficient, and the smaller the value, the more homogeneous the pore-throat sizes are. Vma is the volume percentage of pore-throats larger than 2.5 μm to the total volume of pore-throats. The higher the value, the more developed the large pore-throats are. Higher Vma generally suggests better reservoir physical property, but the connectivity of pore-throat should be considered together to comprehensively determine the quality of reservoir physical property.

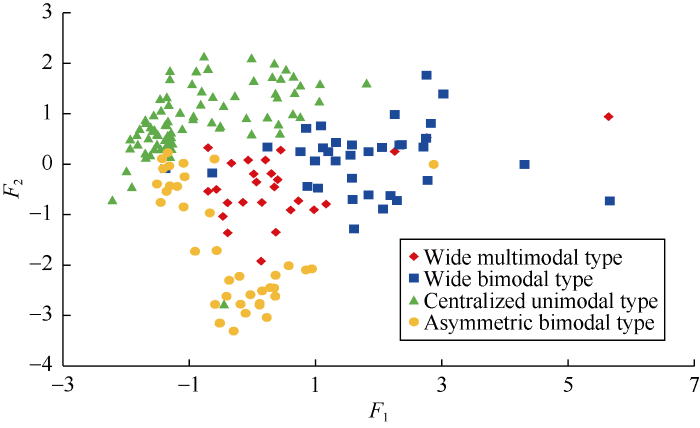

The pore-throat structures were quantitatively characterized by principal component analysis. Principal component analysis, based on the idea of dimensionality reduction, is a multivariate statistic method which converts multiple indicators into several independent indicators. The advantage of this approach is that it can not only reduce the dimensionality of the data, but also retain most information of the raw data. In general, the determined number of principal components (w) depends on its cumulative contribution rate. The cumulative contribution rate needs to be larger than 85% to ensure that w principal components can cover the information of majority of samples. In this work, dimensionality reduction analysis was performed on four sensitive parameters characterizing pore-throat structures, and two principal components, F1 and F2 were selected (with cumulative contribution rate of 86%). The corresponding expressions are as follows:

In the cross plot of the two principal components F1 and F2 (Fig. 5), the centroids of the data points of various types of pore-throat structures are clearly demarcated, and the identification rate of pore-throat structures is up to 80%, demonstrating that the pore-throat structures can be well identified by principal component analysis with quantitative parameters of pore-throat structures. Finally, the sum of total eigenvalues of principal components extracted (S) is first calculated, and then the proportions of eigenvalues of the extracted F1 and F2 to S are taken as the weight of each principal component, respectively. The principal component comprehensive score model, i.e. the quantitative discrimination index (P) for various pore-throat structures is established and the function is as follows:

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Identification results of different pore-throat structures in Carboniferous KT-I layer, North Truva Oilfield.

After calculation, the identification criteria for the four types of pore-throat structures, wide multimodal, wide bimodal, centralized unimodal and asymmetric bimodal types, respectively, are shown in Table 3 and these pore-throat structures can be identified quantitatively according to discrimination index of pore-throat structure P.

Table 3 Quantitative identification criteria for different pore- throat structures of Carboniferous KT-I layer in North Truva Oilfield.

| Pore-throat structure type | P |

|---|---|

| Wide multimodal type | 0.52-0.77 |

| Wide bimodal type | 0.18-0.52 |

| Centralized unimodal type | 0.77-1.00 |

| Asymmetric bimodal type | 0-0.18 |

3. Main factors controlling pore-throat structure differences

Different types of carbonate reservoirs in the Carboniferous KT-I layer of the North Truva Oilfield have obvious differences in pore-throat structure. The main factors causing the differences are closely related to sedimentation, diagenesis and tectonism.

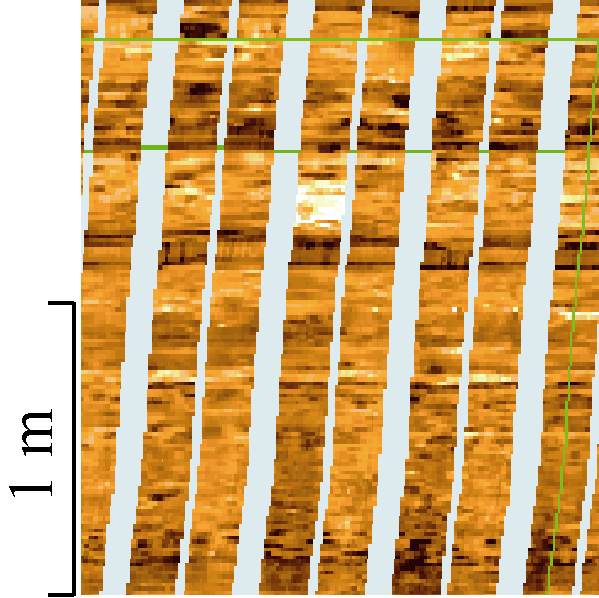

3.1. Sedimentation

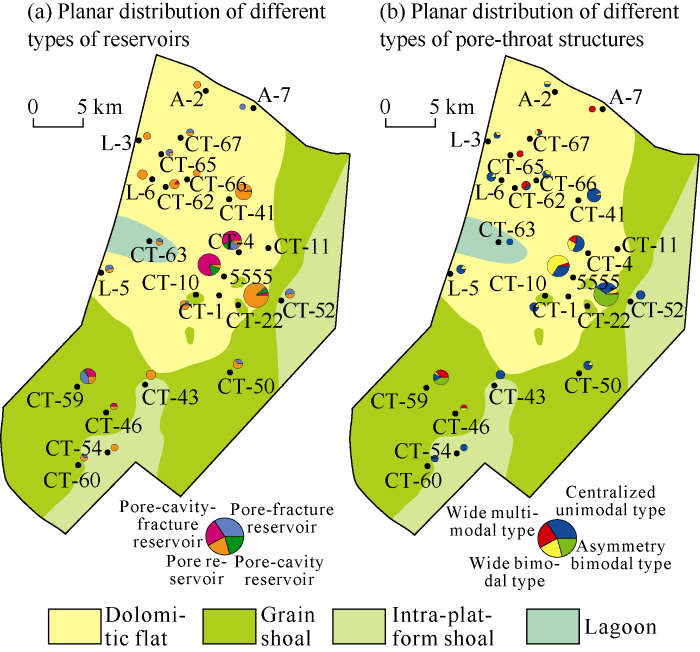

The Carboniferous KT-I layer in the study area is developed in shallow-water carbonate platform environment. The sedimentation controls the rock types and primary porosity, which are the foundation for various types of diagenetic processes and evolution of secondary porosity in the late stage, directly influencing the formation and distribution of different types of reservoirs, ultimately resulting in large differences in microscopic pore-throat structures of the reservoirs (Figs. 6-8). In Fig. 6a, the favorable reservoir types such as pore-cavity- fracture reservoir and pore-cavity reservoir mainly occur in dolomitic flat (such as Well CT-4), and a small number of them are in grain shoal (such as Well CT-59). But the reservoirs in intra-platform shoal and lagoon come in fewer types (such as Well CT-63), among which the pore reservoir is the primary type and the pore-fracture reservoirs are fewer and poorer in physical property in general. As to the pore-throat structure types in various microfacies (Fig. 6b), dolomitic flat has three types of pore-throat structures developed, namely wide multimodal type, wide bimodal type, and centralized unimodal type with better physical properties (Figs. 7 and 8). Grain shoal is most complex in pore-throat structure, with all the four types of pore-throat structures (for example, Well CT-59), but the favorable pore-throat structures gradually reduce (Fig. 8). The other microfacies have relatively monotonous pore-throat structure, mainly centralized unimodal type (Fig. 8), suggesting that the microfacies has a control effect on pore-throat structures (Fig. 6b).

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Planar distribution of different types of reservoirs and pore-throat structures in the Carboniferous KT-I layer of North Truva Oilfield (Bubble size represents the number of samples).

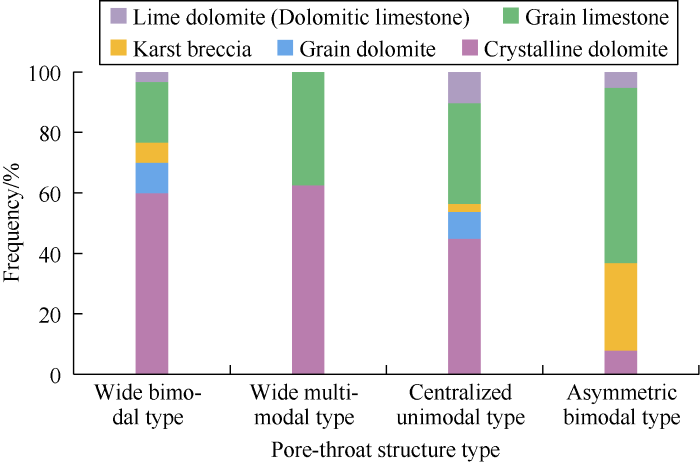

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Distribution of rock types in different pore-throat structures of KT-I layer in the North Truva Oilfield.

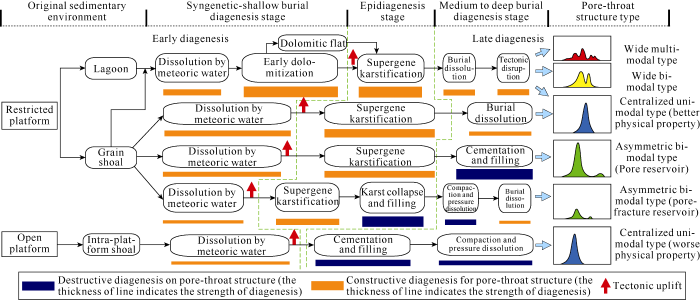

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

The evolution of pore-throat structures under the control of sedimentary environments, main diagenetic processes and tectonism of the Carboniferous KT-I layer in the North Truva Oilfield.

The distribution of various rock types in different types of pore-throat structures (Fig. 7) shows that the development frequencies of dolomite in wide bimodal type, wide multimodal type, centralized unimodal type, asymmetric bimodal type has an obvious decreasing trend in dolomite, while the development frequency of limestone has a significant increase trend. In particular, limestone takes up more than 60% in the asymmetric bimodal type of poor pore-throat structures, which demonstrates that the dolomite plays a constructive role in the formation of favorable pore-throat structures, representing the controlling effect of rock type on pore-throat structures.

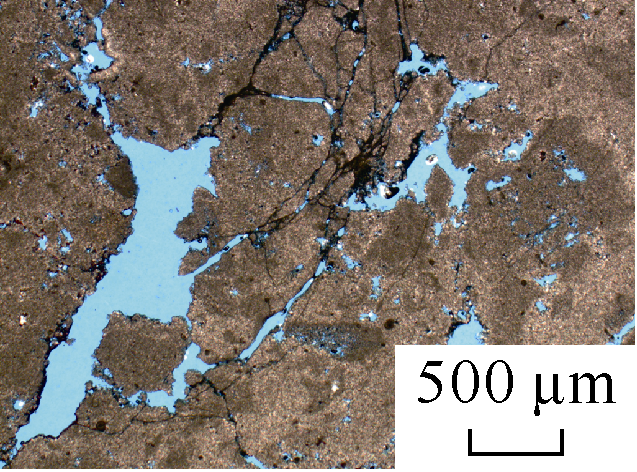

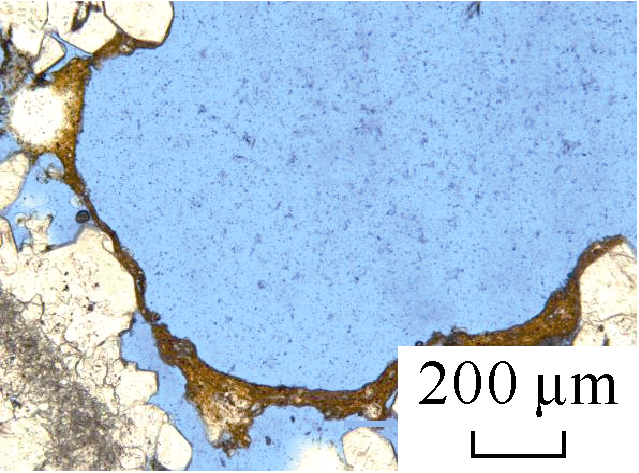

The dolomitic flat consists of mainly crystalline dolomite (77.6%) and a small amount of grain dolomite like bioclast dolomite (16.8%). 74% of the crystalline dolomite samples have residual particles of original rock visible. The residual particles are largely bioclast, foraminifera and fusulinid, indicating the original rock was formed in both high-energy shallow-water environment (grain shoal) and low-energy environment (lagoon) (Fig. 8), and had intergranular (dissolution) pores, visceral foramens, moldic pores and various dissolution pores and caverns developed (Fig. 9), with pores and caverns of centimeter-level on the core (Table 1). The formation of dolomite would inherit these pores, forming reservoir spaces consisting of well-developed pores, dissolved pores and caverns etc. Meanwhile, the replacement of calcite by dolomite, on the one hand, can increase the number of pores, form intercrystalline pores (micro-pores), and improve percolation characteristics of the reservoir[30] (Fig. 9a), on the other hand can provide migration pathways for diagenetic fluids[30] to facilitate the formation of intercrystalline dissolution pores and other dissolution pores and vugs in the later period (Figs. 9c and 9d), and further improve the pore-throat structure of the reservoir. More importantly, dolomite is more resistant to compression and pressure solution than limestone[30,31,32], and thus can effectively protect the pre-exist pore spaces from destruction by compaction.

Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

Microscopic characteristics of reservoir spaces of KT-I layer in the North Truva Oilfield. (a) Well 5555, 2335.24 m, residual foraminiferal micrite dolomite, visceral foramen and intercrystalline micropore; (b) Well A-2, 2887.88 m, sparry oolitic limestone, oolite moldic pore and intragranular dissolution pore; (c) Well A-7, 2669.76 m, silty dolomite, intercrystalline (dissolution) pore, residual dolomite crystal outline after dissolution, pores semi-filled by asphalt; (d) Well CT-4, 2341.66 m, bioclastic micrite dolomite, bead-like dissolution fissure, netted dissolution fissure, forming a fracture-cavity system with dissolved pores and caverns; (e) Well CT-22, 2299.93 m, sparry foraminiferal limestone, intergranular (dissolution) pores and visceral foramen; (f) Well 5555, 2345.72 m, residual bioclastic and silty-crystalline dolomite, intermittent extension of tectonic fracture, semi-filled by dolomite; (g) Well CT-22, 2300.55 m, foraminiferal fusulinid limestone, with vadose silt filling in the intergranular pores and granular cracks; (h) Well CT-59, 2383.09 m, collapsed karst breccia limestone in sharp angular shape, diverse structures and cluttered stacking patterns, with lime in the interbreccia pores and residual intergranular pores and shrinkage cracks.

3.2. Diagenesis

The carbonate reservoirs of Carboniferous KT-I layer in the North Truva Oilfield have undergone various types of diagenetic processes, among which early dolomitization, dissolution, karst collapse and filling, and cementation have the greatest influences on the pore-throat structure of reservoir.

Petrological and geochemical characteristics of dolomite in the study area[26, 33-34] show that the dolomite crystalline grains are fine, mainly micrite, silty-micritic, and silty, low in euhedral degree, subhedral-xenomorphic (Fig. 9), and low in ordering degree (0.336-0.504, and 0.417 on average). The dolomite samples have the values of δ18O of -1.06‰ to 2.45‰, 0.48‰ on average, δ13C of 3.36‰ to 5.94‰, 5.11‰ on average, 87Sr/86Sr ratios of 0.708 29-0.708 75, 0.708 37 on average; average contents of Fe and Mn of 447.52 μg/g and 92.57 μg/g, respectively, luminescent intensity of high, moderate-weak and non-luminous; average contents of Na and K of 198.80 μg/g and 5.89 μg/g, respectively, and higher contents in dolomite than in limestone. Comprehensive analysis of the above data indicates that the origin of dolomite in the study area is seepage-reflux dolomitization. Meanwhile, the paleotemperature of Carboniferous KT-I layer in the study area was calculated by δ18O[35]. The “age effect” needs to be corrected in the KT-I layer as the “age effect” makes the samples before the Mesozoic susceptible to diagenesis[36]. The calculation results show that the paleotemperature of Carboniferous KT-I layer was 3-16 °C (10 °C on average), which proves that the dolomite in the study area was formed in low-temperature environment of early stage. Early dolomitization allowed inheritance and protection part of original porosity[30, 37] which provided initial conditions for various types of dissolution in the later period, so it plays an important role in the formation and protection of favorable reservoirs and pore-throat structures.

The KT-I layer suffered extensive karstification during the supergene stage, making the carbonate rocks of KT-I layer subject to regional exposure, weathering and erosion. Meteoric water leached and dissolved the dolomite and limestone in the weathered crust, resulting in enlarged dissolution of pre-existent pore spaces, and creation of a variety of reservoir spaces in various combinations[38,39], which is the most critical factor for the formation of favorable pore-throat structures (Fig. 8). The duration of shallow diagenesis of the Carboniferous KT-I layer is not long[38], and the medium-deep burial diagenesis has main control on pore- throat structures. The acidic compaction water produced by the Lower Permian dark shale, CO2 and other acidic formation waters had non-fabric- selective dissolution to previous preponderant pore spaces of KT-I layer, leading to enlargement of the pre-existing pores and even dissolution of dolomite crystals into pores and caverns (Fig. 9c), leaving asphalt in the caverns (Fig. 9c and 9d), further improving the pore-throat structure of the reservoir[40] (Fig. 8).

The asymmetric bimodal pore-throat structure mainly occurs in grain limestone (Fig. 7). This kind of limestone has a high content of fusulinid, echinoderms and arenite grains, and well developed visceral foramen, intragranular dissolution pores and moldic pores, with a plane porosity ratio up to 69.2%, so it has the lowest proportion of favorable pore types such as intercrystalline dissolution pore and intergranular dissolution pore (only 15%) among the four types of pore-throat structures (Fig. 10). Supergene karstification is usually associated with intense cementation filling (Fig. 8), for instance, echinoderms secondary overgrowth, syntaxial overgrowth cements and calcite cements fill intergranular pores (Fig. 9e), leading to the reduction of plane porosity ratio of favorable pore types and destruction of connectivity between intergranular pores and visceral foramen, intragranular pores and other types of pores, consequently, the pore-throat structure becomes poorer[12], giving rise to the asymmetric bimodal pore-throat structure in pore reservoirs (Fig. 8).

Fig. 10.

Fig. 10.

Types of reservoir spaces and combination patterns of various reservoir spaces in different pore-throat structures of Carboniferous KT-I layer in the North Truva Oilfield.

While strongly reforming the reservoir, karstification is also likely to cause collapse of reservoir, consequently, with spaces filled, the reservoir would turn poorer in physical property[41] (Table 2, Fig. 9h). This is the case for the pore-throat structure of asymmetric bimodal type developed in pore-fracture reservoir. The reservoir is collapsed karst breccia, and the filling makes the pore-cavity-fracture system originated from karstification filled with breccia and marl. Even though a small amount of shrinkage cracks and dissolution fissures are generated in the later stage due to compaction and dissolution, the collapse filling with extremely intense heterogeneity significantly reduces the connectivity degree between the favorable pore-cavity-fracture system and the main (micropores) pores (Fig. 9h), resulting in poor pore-throat structures (Fig. 8).

3.3. Tectonism

The tectonic movement in the Late Carboniferous Hercynian caused overall uplift of the eastern margin of the Pre-caspian Basin[42]. The Ural orogeny in the end of the Permian and the compaction and pressure dissolution after deep burial produced various types of fractures[43] (Fig. 9d, 9f-9h), among which the dissolution fissure is the most developed (Fig. 3a) and mainly appears in dolomite because dolomite is more brittle than limestone and is prone to rupture[44] to generate tectonic fractures and granular cracks (Figs. 8, 9f, 9g). Diagenetic fluids could dissolve and expand these previous fractures of tectonism origin to form dissolution fissures (Fig. 9d). Dissolution fissures and tectonic fractures with low filling degree can not only contribute more reservoir spaces, but more importantly, connect pores and dissolution cavities, remarkably improving the physical property and pore-throat structure of reservoir. Fractures are well developed in wide bimodal, wide multimodal and centralized unimodal types of pore-throat structure reservoirs, so these reservoirs are better in physical property, while fractures are poorly developed in reservoir with asymmetric bimodal type pore structure, so this kind of reservoir has poorer physical property (Fig. 10, Table 2).

3.4. Main factors controlling pore-throat structure differences

Based on the above analyses, sedimentation, diagenesis, and tectonism worked together to give rise to pore-throat structure differences. Early dolomitization, karstification, and tectonism in the favorable sedimentary facies are the key factors to improve pore-throat structure (Fig. 8). Early dolomitization and subsequent karstification reformed grain shoal and lagoon in restricted platform, giving rise to favorable pore-throat structures such as wide bimodal and wide multimodal types. The grain shoal without dolomitization experienced karstification, developing secondarily favorable pore-throat structure (centralized unimodal type with better physical property). But in the grain shoal primarily subjected to cementation, karst collapse and filling resulted in the pore-throat structure of asymmetric bimodal type with the worst physical property. As the intra-platform shoal in the open platform is far away from the top of the KT-I layer, it hasn’t been reformed by karstification and has the centralized unimodal type pore-throat structure with poorer physical property.

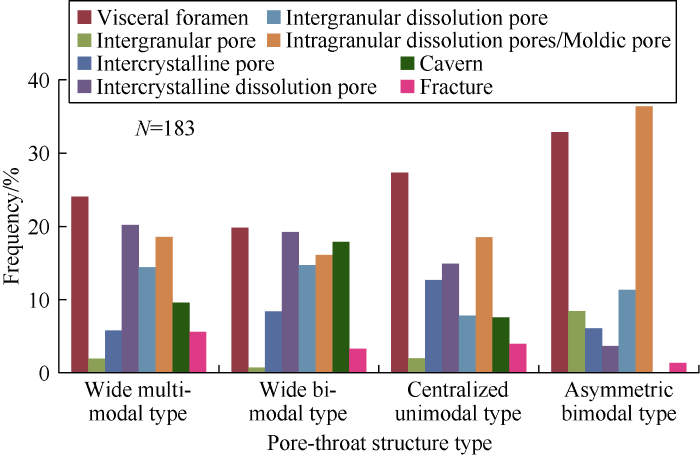

Although sedimentation, diagenesis, and tectonism have significant differences in intensity, stage, and effectiveness on carbonate reservoirs of the KT-I layer (Fig. 8), the final result is the formation of various reservoir spaces in various combination patterns under their joint actions (Fig. 10). Therefore, the combination pattern of reservoir spaces is the main factor controlling the difference in pore-throat structures. With different types of reservoir spaces and different combination patterns of reservoir spaces, different types of reservoirs have different pore-throat combination types (Fig. 11), which in turn control the microscopic heterogeneity of different types of reservoirs (Figs. 11 and 12). The pore type reservoir has the strongest heterogeneity and all the four types of pore-throat structures. The pore-cavity-fracture reservoir and pore-fracture reservoir are second in heterogeneity, and have three types of pore-throat structures; the former has more types of favorable pore-throat structures than the latter (only wide multimodal type), and the latter has the worst pore-throat structure type. The pore-cavity reservoir with the weakest heterogeneity has only two types of pore-throat structures.

Fig. 11.

Fig. 11.

Distribution of pore-throat structure types in different types of reservoirs of the Carboniferous KT-I layer in the North Truva Oilfield (N=183).

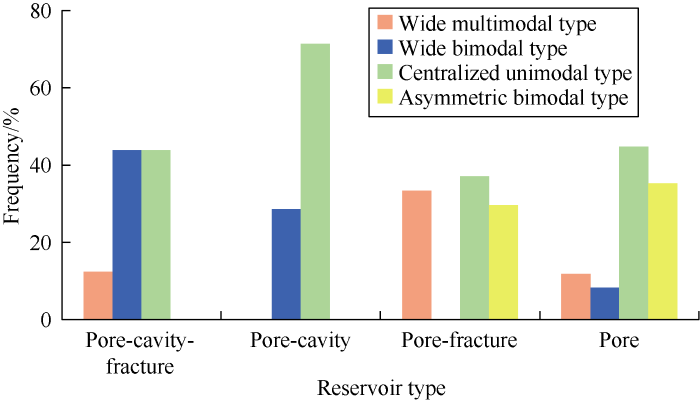

4. Influence of pore-throat structure on porosity-permeability relationship of reservoir

Complex pore-throat structures are the key factor controlling the physical property of carbonate reservoir[5, 7-12, 37], and each type of reservoir has multiple types of pore-throat structures (Figs. 11 and 12). After subdividing the pore-throat structures, it can be clearly seen that the capillary pressure curves and pore-throat radius distribution curves of different pore-throat structures in different reservoirs exhibit multiple distribution regularities that can tell them apart (Fig. 12). Although the porosity-permeability relationships of different types of carbonate reservoirs in the study area have distinctive characteristics, the complex pore-throat structures make the porosity-permeability relationships of reservoirs complicated (Fig. 3c). Therefore, it is necessary to further clarify the control of the pore-throat structures on the porosity-permeability relationships of reservoirs, to guide the establishment of an accurate permeability calculation model.

Fig. 12.

Fig. 12.

Capillary pressure curves and pore-throat radius distributions of different types of reservoirs in the Carboniferous KT-I layer of the North Truva Oilfield.

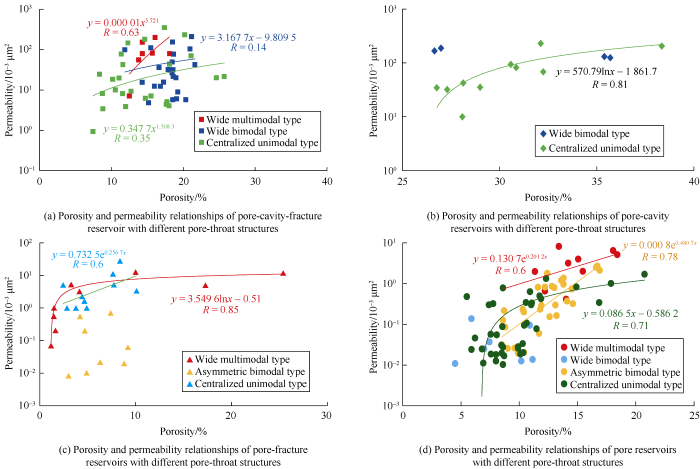

The pore-cavity-fracture reservoir has pores, caverns and fractures developed. The complicated reservoir spaces configuration makes the pore-throat structures of this kind of reservoir very complex, and the porosity and permeability data points of this kind of reservoir show discrete distribution characteristic and poor correlation (Fig. 3c, R=0.34). After subdividing the pore-throat between porosity and permeability (R=0.63) (Fig. 13), while the reservoirs with wide bimodal (R=0.14) and centralized unimodal (R=0.35) types still show poor correlation between porosity and permeability, which is closely related to the intense heterogeneity of pore-throat structures of pore-cavity- fracture reservoir. For example, as the reservoir with wide bimodal pore structures has both favorable reservoir spaces like intercrystalline dissolution pores and caverns and non- favorable reservoir spaces like foramens developed (Fig. 10), which come into complex configuration, making the pore- throat structures complicate (Fig. 9d), and resulting in its porosity permeability relationship most complex among the reservoirs of the four pore-throat structures (Fig. 13a).

structures, the reservoir with wide multimodal type pore structures shows better correlation

Fig. 13.

Fig. 13.

Porosity and permeability relationships after subdividing pore-throat structures of different reservoirs of the Carboniferous KT-I layer in the North Truva Oilfield.

With pores and caverns but no fractures developed, the pore-cavity reservoir is less complex in pore-throat structure and weaker in heterogeneity than pore-cavity-fracture reservoir. Therefore, this kind of reservoir has slightly better correlation between porosity and permeability than pore-cavity- fracture reservoir (Fig. 3c, R=0.49). After subdividing the pore-throat structures, it is found the reservoir with centralized unimodal pore-throat structures shows weaker complexity and better correlation between porosity and permeability (R = 0.81), whereas there are few samples points of the reservoir with wide bimodal pore-throat structures, the relationship between porosity and permeability of this kind of reservoir can’t be worked out (Fig. 13b).

The pore-fracture reservoir has pores and fractures developed and the fractures of different types differ in pore-throat structure. For instance, tectonic fractures are straight while dissolution fissures are tortuous. Different types of fractures combine with pores into complex spatial configurations, making this kind of reservoir poor in porosity-permeability correlation in general (Fig. 3c, R=0.43). After subdividing the pore-throat structures, the reservoirs with wide multimodal and centralized unimodal pore-throat structures show better porosity-permeability correlations with R values of 0.85 and 0.6 respectively, whereas the reservoir with asymmetric bimodal pore-throat structures has random distribution of combination patterns of reservoir spaces from karst collapse and strong heterogeneity (Fig. 9h), making its porosity and permeability relationship very complicate. Meanwhile, this demonstrates that not every type of pore-throat structure can set up a good correlation between porosity and permeability (Fig. 13c).

Pore reservoirs mainly develop pores. Even though without caverns and fractures developed, it has the most types of pore-throat structures among the four types of reservoirs, indicating it has intense microscopic heterogeneity. The porosity and permeability data points of this kind of reservoir are relatively concentrated and show better correlation (R=0.72). After subdividing the pore-throat structures, except the reservoir with wide bimodal type pore-throat structure, the remaining three types of reservoirs with wide multimodal, centralized unimodal and asymmetric bimodal pore-throat structures all can see good correlation between porosity and permeability (Fig. 13d). It seemingly contradicts the understanding that “the more intense the reservoir microscopic heterogeneity is, the more complex the porosity-permeability relationship will be". In fact, it is because that the combination patterns of reservoir spaces are the main controlling factor for the difference in pore-throat structure; moreover, the pore-throat structure of pore reservoir is composed of the majority of poor pore types (such as visceral foramen and intragranular dissolution pore) and a minority of favorable pore types (such as intercrystalline dissolution pore and intergranular dissolution pore), so its pore-throat structure is less complicate than that of the pore-cavity-fracture reservoir with all reservoir space types like pores, caverns and fractures (Figs. 10 and 11). Therefore, the pore-cavity-fracture reservoir with more complex pore-throat structures is more complicated in porosity and permeability relationship (Fig. 13a), bringing challenges to establishment of accurate permeability model for this kind of reservoir.

From the porosity and permeability relationships of the four kinds of reservoirs after subdividing pore-throat structures, we reached two findings: (1) After subdividing pore-throat structures of different reservoirs, different types of pore-throat structures show good partition, porosity and permeability data points of different pore-throat structures show discernable centroids, reflecting the control of pore-throat structures on porosity-permeability relationships. (2) After subdividing pore-throat structures, the porosity-permeability relationships of approximately 75% of samples of different pore-throat structures show improvement, and the minority of samples shows less improvement, which is related to the insufficient data available of overseas oilfields (only 183 samples available for high-pressure mercury intrusion test to study the pore-throat structure of different types of reservoirs). In comparison, carbonate reservoir geologist, Lønøy[10] collected about 3000 samples and established porosity and permeability relationships of various pore-throat structures based on pore type, pore size and sorting. According to the results of his research, the porosity and permeability relationships of all pore-throat structures have been significantly improved, demonstrating that establishing the porosity and permeability relationships of reservoirs by subdividing pore-throat structures is an effective approach to improve the calculation accuracy of permeability when there are sufficient samples available.

In view of the strong influences and complex controls of pore-throat structures on porosity and permeability relationships of different types of carbonate reservoirs, it is necessary to further reveal the effects of diverse pore-throat structures on reservoir permeability. The specific method adopted in this study is as followed: Firstly, the parameters of various types of reservoirs have best correlation with permeability were selected from parameters representing reservoir storage capacity (ϕ), pore-throat size (Rav, Dav, Rmax, R5-R90, Vma, Vme, Vmi, Vma+me, etc.), pore-throat sorting (Sp, C, Skp, Kp, α, etc.) and pore connectivity (Vpt, We, Smin, etc.) by using the single factor analysis method. Secondly, the main controlling factors on the permeability of various types of reservoirs were quantitatively analyzed by gray correlation analysis[45] to find out the priority orders of influences of different pore-throat structure parameters on the permeability of various types of reservoirs, in the hope to provide technical guidance for the improvement of calculation accuracy of permeability. The permeability of pore-cavity-fracture reservoir is mainly affected by the proportion of large pore throat, variation coefficient and apparent pore-throat volume ratio, which represent the development degree of different pore-throats, pore-throat sorting and pore connectivity respectively (Table 4). It demonstrates that intense dissolution can form a pore-throat network system with primarily large pore throats and disordered distribution of pore throats of different sizes, and the fractures connecting the dissolution pores and caverns can greatly increase the permeability of pore-cavity- fracture reservoir. The permeability of pore-cavity reservoir is mainly controlled by R5, the proportion of large pore throats and porosity which represent pore-throat size, the development degree of different pore-throats and reservoir storage capacity respectively (Table 4). The large number of large pore throats and large reservoir spaces generated by strong dissolution contribute the most to the permeability of pore-cavity reservoir. The permeability of pore-fracture reservoir is primarily controlled by porosity, Smin and homogeneity coefficient which represent reservoir storage capacity, pore connectivity and pore-throat sorting respectively (Table 4). This indicates that the superimposition of fractures and matrix pore spaces can significantly improve connectivity and flow capacity of pore-fracture reservoir. The permeability of pore reservoir is affected by the mean radius of pore-throats, the proportion of large-to-medium pore throats and porosity which represent pore throat size, the development degree of different pore throats and the reservoir storage capacity respectively (Table 4). This shows that the higher the proportion of large pore throats and the larger the reservoir spaces are, the better the flow capacity of the pore reservoir will be.

Table 4 Quantitative evaluation by grey correlation method on the main controlling factors of permeability of different types of reservoirs in the Carboniferous KT-I layer of the North Truva Oilfield.

| Reservoir type | Influencing parameter types, grey correlation degree and ranking | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reservoir storage capacity | Grey correlation degree and ranking | Pore- throat size | Grey correlation degree and ranking | The development degree of different pore-throats | Grey correla- tion degree and ranking | Pore- throat sorting | Grey correlation degree and ranking | Pore connec- tivity | Grey correlation degree and ranking | |

| Pore-cavity- fracture reservoir | ϕ | 0.587 5(5) | R35 | 0.595 0(4) | Vma | 0.695 9(1) | C | 0.657 1(2) | Vpt | 0.612 7(3) |

| Pore-cavity reservoir | ϕ | 0.561 6(3) | R5 | 0.777 3(1) | Vma | 0.683 6(2) | C | 0.522 6(5) | We | 0.539 7(4) |

| Pore-fracture reservoir | ϕ | 0.701 4(1) | Rav | 0.620 0(5) | Vma | 0.637 6(4) | α | 0.656 7(3) | Smin | 0.685 4(2) |

| Pore reservoir | ϕ | 0.573 5(3) | Dav | 0.720 1(1) | Vma+me | 0.622 6(2) | C | 0.509 4(5) | We | 0.552 4(4) |

5. Conclusions

Based on in-depth analysis of the characteristics of frequency distribution curve of pore-throat radius, a set of classification and description method for pore-throat structures suitable for Carboniferous carbonate reservoirs in the eastern margin of Pre-caspian Basin has been established, and four kinds of pore-throat structures for complex carbonate rocks have been identified: wide multimodal, wide bimodal, centralized unimodal and asymmetric bimodal types respectively. Based on the multi-information fusion technology, the parameters sensitive to pore-throat structures were picked out by cross-plot method, and the identification index for pore-throat structures has been worked out by the principal component analysis approach, realizing quantitative identification of the four types of pore-throat structures.

The influences of sedimentation, diagenesis and tectonism on the differences in pore-throat structure have been figured out: the early dolomitization in favorable sedimentary facies is an important foundation for the formation of favorable pore- throat structures. The supergene karstification is the key factor for the development of favorable pore-throat structure. Tectonic rupture can further improves pore-throat structure, while the cementation and karst collapse and filling are the decisive factors making the pore-throat structure worse. It is found that the combination patterns of reservoir spaces formed by the superimposed reformations of sedimentation, diagenesis and tectonism are the main controlling factor on the differences in pore-throat structure. The pore reservoir with all the four types of pore-throat structures has the strongest microscopic heterogeneity. The pore-cavity-fracture and pore-fracture reservoirs follow, and the pore-cavity reservoir has weaker heterogeneity.

It is revealed that the development of multiple sorts of pore-throat structures is the key factor leading to the poor correlation between porosity and permeability of various reservoirs. Establishing porosity and permeability relationships of various reservoirs by subdividing pore-throat structure types is an effective method to improve the calculation accuracy of permeability. By using single factor analysis and gray correlation analysis jointly, the priority orders of influences of different pore-throat structure parameters on the permeability of various types of reservoirs have been sorted out, in the hope to provide technical guidance for the improvement of calculation accuracy of carbonate reservoir permeability.

Nomenclature

C—variation coefficient, dimensionless;

Dav—mean radius of pore-throats, μm;

Dr—relative sorting coefficient, dimensionless;

F1—first principal component, dimensionless;

F2—second principal component, dimensionless;

K—permeability, 10-3 μm2;

Kp—pore-throat kurtosis, dimensionless;

N—sample numbers;

P—quantitative identification index for different pore-throat structures, dimensionless;

Pc—capillary pressure, MPa;

R—correlation coefficient, dimensionless;

R5, R10, …, R35, …, R90—corresponding pore-throat radius when mercury saturation reaches 5%, 10%, ..., 35%, ..., 90%, μm;

Rav—average pore-throat radius, μm;

Rmax—maximum pore-throat radius, μm;

S—sum of total eigenvalues of extracted principal components, dimensionless;

SHg—mercury saturation, %;

Skp—pore-throat skewness, dimensionless;

Smin—percentage of minimum unsaturated pore-throat volume, %;

Sp—sorting coefficient, dimensionless;

Vpt—apparent pore-throat volume ratio, dimensionless;

Vma—percentage of large pore-throats, %;

Vme—percentage of medium pore-throats, %;

Vmi—percentage of small pore-throats, %;

Vma+me—Percentage of medium and large pore-throats, %;

w—number of principal components;

We—efficiency of mercury withdrawal, %;

α—homogeneity coefficient, dimensionless;

ϕ—porosity, %.

Reference

Wettability challenges in carbonate reservoirs

Technological progress and development directions of PetroChina overseas oil and gas field production

Carbonate reservoirs: Porosity and diagenesis in a sequence stratigraphic framework

Complex relationship between porosity and permeability of carbonate reservoirs and its controlling factors: A case of platform facies in Pre-Caspian Basin

carbonate petroleum reservoirs: A global perspective on porosity-depth and porosity-permeability relationships

DOI:10.1306/11230404071 URL [Cited within: 1]

Permeability-porosity relationships in sedimentary rocks

Quantification of pore structure and its effect on sonic velocity and permeability in carbonates

Progress of research on permeability of carbonate rocks

Making sense of carbonate pore systems

DOI:10.1306/03130605104 URL [Cited within: 3]

Carbonate rock characterization and modeling: Capillary pressure and permeability in multimodal rocks: A look beyond sample specific heterogeneity

DOI:10.1306/02071211124

URL

[Cited within: 1]

Carbonate rocks are known for their heterogeneity and petrophysical complexity. This commonly leads to large uncertainties in reservoir models that are intended to predict fluid storage and fluid flow. In this article, focus is given to the characterization of pore systems at core-plug scale to provide improved models for permeability and saturation prediction. These methods fall under a wider rock-typing workflow.

We examine the use of mercury-air capillary pressure data for rock-type definition and for predicting saturation and permeability. We present new methods for modeling saturation in rocks with multimodal pore-throat size distributions. The methods bear similarity to those previously published but with some key differences, mainly by relating the capillary pressure data to the pore systems representative for a rock type. We also present a new method for relating permeability to pore-throat sizes that is more versatile, in that it can be employed for all types of pore-throat size distributions-unimodal or multimodal. We demonstrate that a normalized pore-throat radius parameter forms a straight line relationship with permeability over six orders of magnitude. It appears to be a fundamental property for all pore systems so far examined. The wider implication of the workflows presented is that they offer better integration between the methods used for saturation prediction and the methods used for permeability prediction, something that is desirable for all subsurface studies.

Influential factors of pore structure and quantitative evaluation of reservoir parameters in carbonate reservoirs

Pore texture evaluation of carbonate reservoirs in Gasfield A, Turkmenistan

Pore structure study of carbonate reservoir

Marine carbonate reservoir characteristics of the Middle Ordovician Majiagou Formation in Ordos Basin

Pore structure characteristics and control factors of carbonate reservoirs: The Middle-Lower Cretaceous formation, AI Hardy cloth Oilfield, Iraq

Diagenesis in carbonate reservoir and pore structure characteristic from the Ordovician Ma51 sub-member reservoir in the northern Jingbian Gasfield

Pore structure characteristics and control factors of carbonate reservoirs: The Cretaceous Mishrif Formation, Halfaya oilfield, Iraq

Pore types, origins and control on reservoir heterogeneity of carbonate rocks in Middle Cretaceous Mishrif Formation of the West Qurna Oilfield, Iraq

Quantitative characterization of carbonate pore systems by digital image analysis

Incorporating capillary pressure, pore throat aperture radii, height above free-water table, and Winland r35 values on Pickett plots

Relationships between permeability, porosity and pore throat size in carbonate rocks using regression analysis and neural networks

Effect of pore structure on electrical resistivity in carbonates

The electrical resistivity log has proven to be a powerful tool for lithology discrimination, correlation, porosity evaluation, hydrocarbon indication, and calculation of water saturation. Carbonate rocks develop a variety of pore types that can span several orders of magnitude in size and complexity. A link between the electrical resistivity and the carbonate pore structure has been inferred, although no detailed understanding of this relationship exists.

Seventy-one plugs from outcrops and boreholes of carbonates from five different areas and ages were measured for electrical resistivity properties and quantitatively analyzed for pore structure using digital image analysis from thin sections. The analysis shows that in addition to porosity, the combined effect of microporosity, pore network complexity, pore size of the macropores, and absolute number of pores are all influential for the flow of electric charge. Samples with small pores and an intricate pore network have a low cementation factor, whereas samples with large pores and a simple pore network have high values for cementation factor. Samples with separate-vug porosity have the highest cementation factor.

The results reveal that (1) in carbonate rocks, both pore structure and the absolute number of pores (and pore connections) seem more important in controlling the electrical resistivity, instead of the size of the pore throats, as suggested by previous modeling studies; (2) samples with high resistivity can have high permeability; large simple pores facilitate flow of fluid, but fewer numbers of pores limit the flow of electric charge; and (3) pore-structure characteristics can be estimated from electrical resistivity data and used to improve permeability estimates and refine calculations of water saturation.

Electrical and fluid flow properties of carbonate microporosity types from multiscale digital image analysis and mercury injection

Pore structure and fractal analysis of Lower Carboniferous carbonate reservoirs in the Marsel area, Chu-Sarysu Basin

Geochemical characteristics and genetic model of dolomite reservoirs in the eastern margin of the Pre-Caspian Basin

Exploration at the eastern edge of the Precaspian Basin: Impact of data integration on Upper Permian and Triassic prospectivity

Stress sensitive experiments for abnormal overpressure carbonate reservoirs: A case from the Kenkiyak low-permeability fractured-porous oilfield in the littoral Caspian Basin

A new permeability calculation method using nuclear magnetic resonance logging based on pore sizes: A case study of bioclastic limestone reservoirs in the A oilfield of the Mid-East

The genetic types and distinguished characteristics of dolostone and the origin of dolostone reservoirs

Carbonate porosity versus depth: A predictable relation for South Florida

Carbonate reservoir characterization: An integrated approach

Geochemical characteristics of the Carboniferours KT-I interval dolostone in eastern margin of coastal Caspian Sea Basin

Characteristics and development mechanism of dolomite reservoirs in North Truva of Eastern Pre-Caspian Basin

The measurement of oxygen isotope paleotemperatures: TONGIORGI E. Stable isotopes in oceanographic studies and paleotemperatures

Isotopic composition and environmental classification of selected limestones and fossils

Porosity-permeability relationships in interlayered limestone- dolostone reservoirs

Paleogeomorphology recovery and reservoir prediction of Upper Carboniferous in M Block, Pre-Caspian Basin

Major factors controlling the development of marine carbonate reservoirs

Paleocave carbonate reservoirs: Origins, burial-depth modifications, spatial complexity, and reservoir implications

Petroleum geology of superimposed petroliferous Pre-Caspian Basin and hydrocarbon accumulation mechanism in pre-salt petroleum system of the east Pre-Caspian Basin

Development and genetic mechanism of complex carbonate reservoir fractures: A case from the Zanarol Oilfield, Kazakhstan

Discussion on the development models of structural fractures in the carbonate rocks

Main controlling factors of productivity and development strategy of CBM wells in Block 3 on the eastern margin of Ordos Basin