Introduction

1. Recognition of several statistical laws

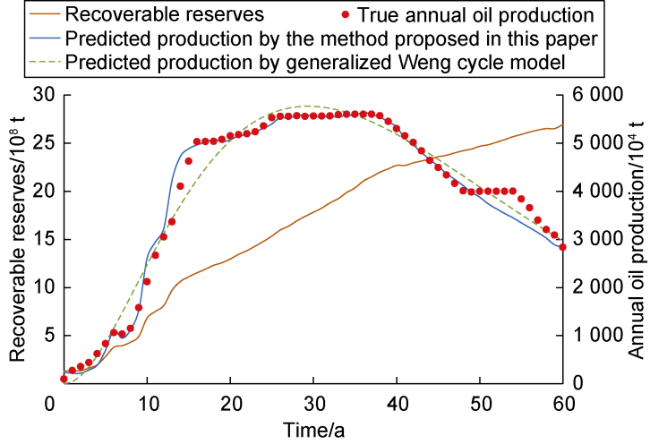

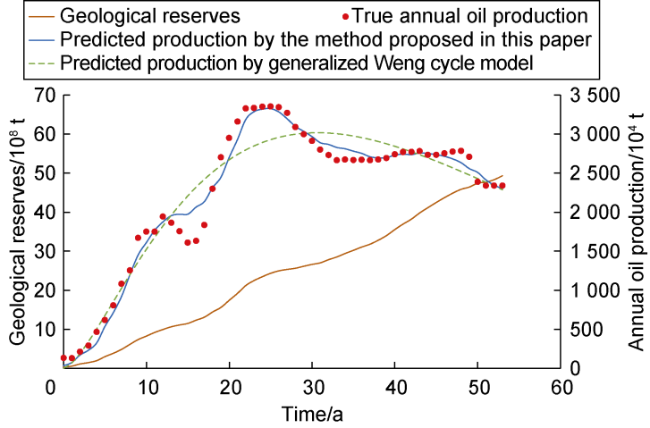

1.1. Production evolution pattern based on recoverable reserves

Fig. 1. Comparison of predicted production by the production evolution model and actual production of Daqing oilfield. |

Fig. 2. Comparison of predicted production by the production evolution model and actual production of Shengli oilfield. |

Table 1. Comparison of the production evolution equations of different oilfields obtained by using the model of this paper and the generalized Weng cycle model |

| Oilfield | Generalized Weng cycle model | Model in this paper | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Production evolution equation | Correlation coefficient | Production evolution equation | Correlation coefficients | |

| Daqing | Q=46.7t2e-t/14.5 | 0.976 | Q=136.6Nr(t)1.7e-0.04t | 0.988 |

| Shengli | Q=74.5t1.5e-t/20.1 | 0.913 | Q=0.000 89N(t)1.31e-0.046t | 0.978 |

| Romanshkin | Q=15.4t3.2e-t/6.0 | 0.949 | Q=0.7N(t)1.0e-0.1t | 0.955 |

| East Texas | Q=2 342t0.1e-t/27.4 | 0.897 | Q=3.1N(t)0.6e-0.03t | 0.945 |

| Zhongyuan | Q=116.6t1.2e-t/9.1 | 0.930 | Q=0.003N(t)1.25e-0.08t | 0.958 |

| Jiangsu | Q=0.4t2.5e-t/11.8 | 0.929 | Q=0.02N(t)1.0e-0.04t | 0.962 |

| Jianghan | Q=34.1t0.52e-t/39.4 | 0.806 | Q=0.001N(t)1.56e-0.05t | 0.907 |

| Henan | Q=202.9t0.18e-t/40.6 | 0.856 | Q=0.78Nr(t)0.72e-0.04t | 0.925 |

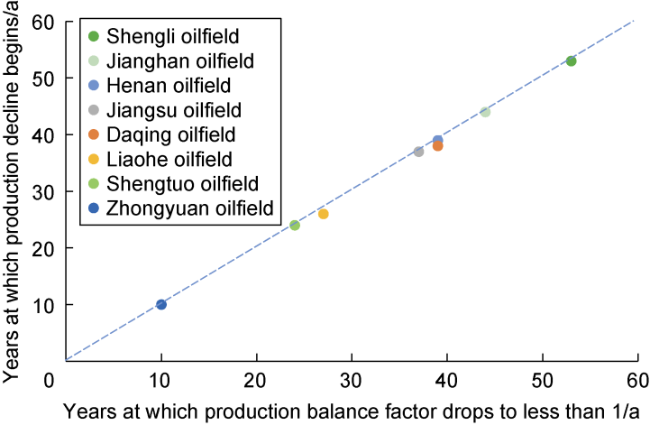

1.2. Matching law of production decline and reserve- production imbalance

Fig. 3. Comparison of the beginning years of oil production decline and those with reserve-production balance factor less than 1 in different oilfields. |

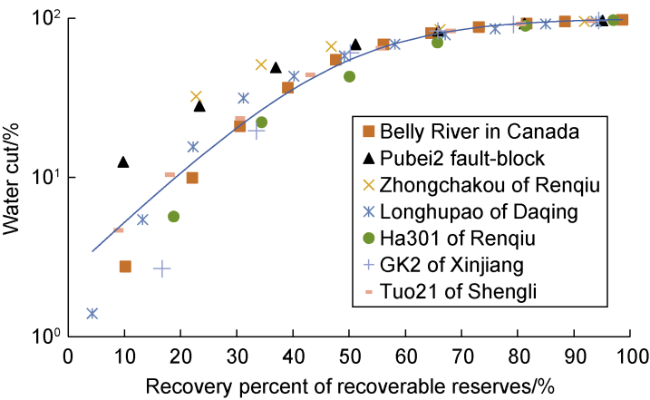

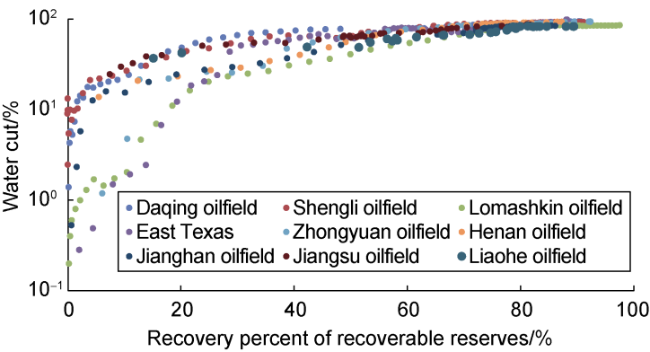

1.3. Matching law between water cut and recovery percent of recoverable reserves

1.3.1. Relationship between water cut and recovery percent of recoverable reserves based on relative permeability curve

Fig. 4. Relationship between water cut and recovery percent of recoverable reserves based on relative permeability curves. |

1.3.2. Relationship between water cut and recovery percent of recoverable reserves based on production data

Fig. 5. Relationship between water cut and recovery percent of recoverable reserves in different oilfields. |

2. Production evolution model and development stage division method

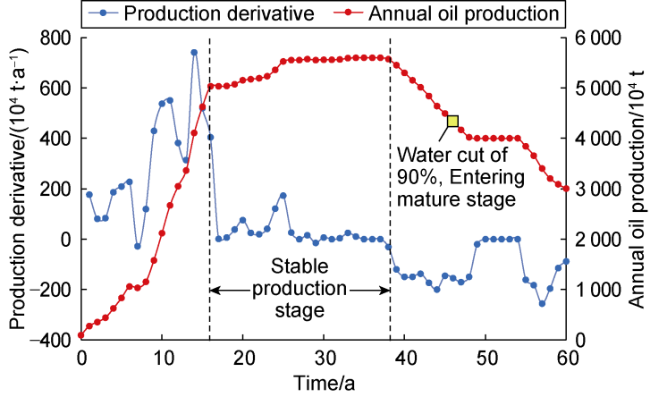

2.1. Methods determining the demarcation points of the development stage

2.1.1. Method determining the initial point of stable production stage

Fig. 6. Variations of production derivative and annual oil production with development time of Daqing oilfield. |

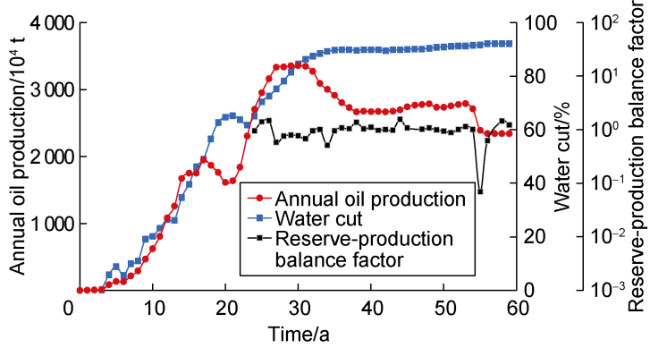

2.1.2. Method determining the initial point of production decline stage

Fig. 7. Variations of annual oil production, water cut and reserve-production balance factor of Shengli oilfield with development time. |

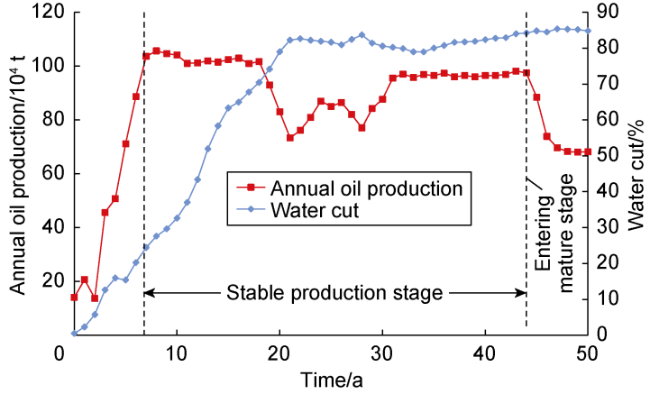

2.2. Several typical patterns of production evolution

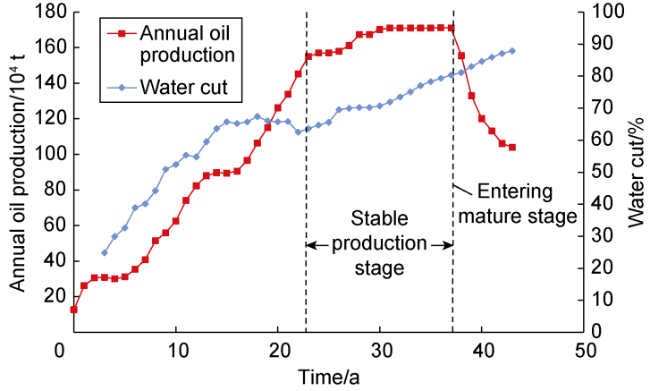

Fig. 8. Variations of annual oil production and water cut of Jianghan oilfield with development time. |

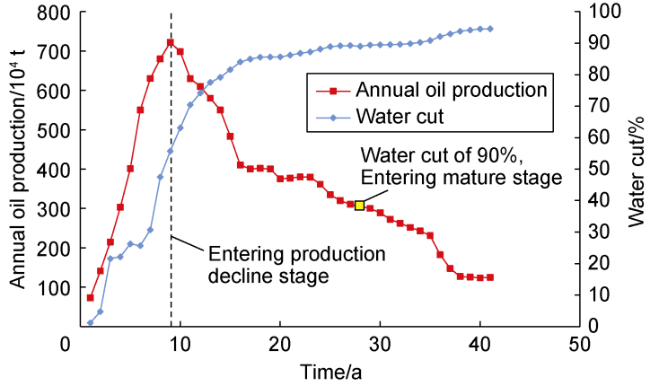

Fig. 9. Variations of annual oil production and water cut of Jiangsu oilfield with development time. |

Fig. 10. Variations of annual oil production and water cut of Zhongyuan oilfield with development time. |

2.3. Connotation and criterion of mature oilfield

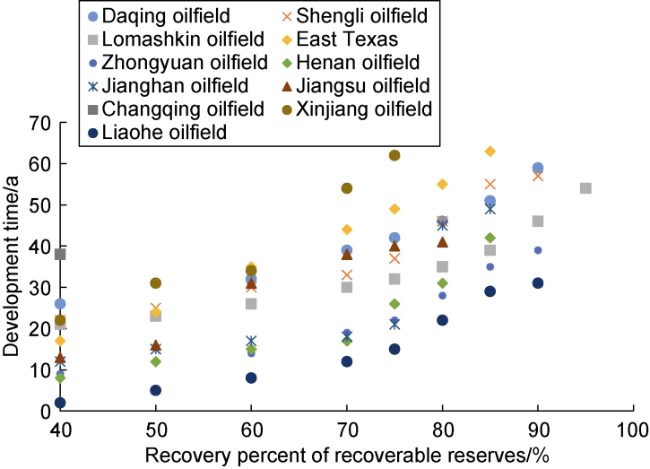

Fig. 11. Relationship between the recovery percent of recoverable reserves and development time of different oilfields. |

Table 2. Criterion of several typical mature oilfields |

| Oilfield | Years when reserve- production balance factor reduces to less than 1/a | Years when water cut reaches 90% or recovery percent of recoverable reserves reaches 80%/a | Years when the oilfield becomes mature/a | Recovery percent of recoverable reserves when oilfield entering mature stage/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daqing | 39 | 46 | 46 | 80.4 |

| Shengli | 53 | 46 | 53 | 82.4 |

| Lomashkin | 25 | 35 | 35 | 80.5 |

| East Texas | 3 | 59 | 59 | 82.7 |

| Zhongyuan | 9 | 28 | 28 | 78.8 |

| Henan | 39 | 31 | 39 | 79.0 |

| Jianghan | 44 | 45 | 45 | 80.6 |

| Jiangsu | 37 | 41 | 41 | 81.0 |

3. Analysis of typical oilfields

Table 3. Development time and recovery percent of recoverable reserves of different stages for some oilfields |

| Oilfield | Production growth stage | Stable production stage | Recovery percent of recoverable reserves at production decline stage/% | Recovery percent of recoverable reserves at mature stage/% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year/a | Recovery percent of recoverable reserves/% | Year/a | Recovery percent of recoverable reserves/% | |||

| Daqing | 16 | 13.0 | 23 | 56.0 | 31.0 | 19.6 |

| Shengli | 27 | 53.1 | 26 | 29.3 | 17.6 | 17.6 |

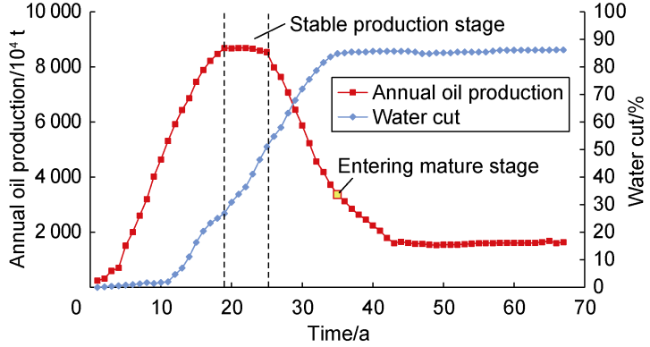

| Lomashkin | 19 | 35.5 | 6 | 14.4 | 50.1 | 19.5 |

| East Texas | 3 | 8.0 | 0 | 0 | 92.0 | 17.3 |

| Zhongyuan | 9 | 43.3 | 0 | 0 | 56.7 | 21.2 |

| Henan | 3 | 12.4 | 36 | 68.2 | 19.4 | 19.4 |

| Jianghan | 7 | 19.2 | 37 | 60.1 | 20.7 | 19.4 |

| Jiangsu | 23 | 51.0 | 14 | 17.7 | 31.3 | 19.0 |

Fig. 12. Variations of annual oil production and water cut with development time of the Romanshkin oilfield. |