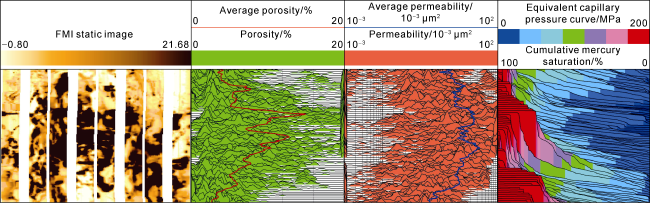

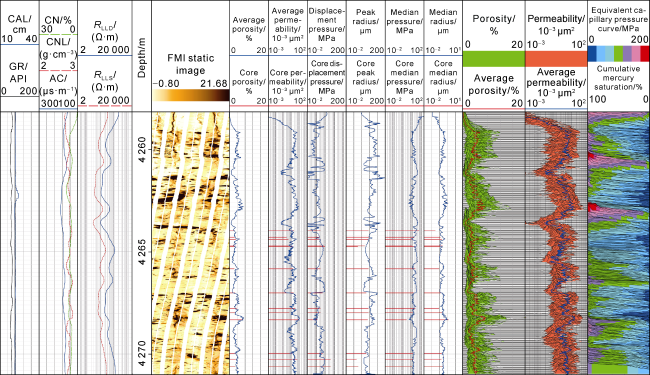

Formation micro-resistivity image (FMI) is a logging method that measures the resistivity of borehole wall by current. The FMI instrument has the sampling interval of 0.25 cm (0.1 in) in depth and circumferential direction, with the instrument resolution of 0.5 cm (0.2 in). The FMI log is used to qualitatively identify the geological features (e.g. bedding, fractures, and dissolved pores/vugs) of the strata around the borehole wall. Based on FMI processing technology, parameters such as fracture porosity, opening degree, the linear density of fractures, the plane porosity of dissolved pores/vugs, and other parameters of the reservoirs can be quantified

[17⇓-19]. Any one of these parameters is a comprehensive response to reservoir heterogeneity at a specific measuring depth. Newsberry et al.

[20] and Akbar et al.

[21] calculated the porosity within the measurement range of microelectrodes based on Archie's equation, and displayed the heterogeneity of reservoir porosity in the measured interval by using a two-dimensional porosity spectrum, thus expanding the application of FMI in reservoir evaluation. Based on the distribution of porosity spectrum, the primary and secondary porosities and their distribution in carbonate reservoirs can be characterized

[22-23], and the correlation between them and oil and gas production data is reflected

[24-25]. Li et al.

[26] classified the reservoirs and evaluated the distribution of favorable reservoirs according to the mean and variance of porosity spectrum, together with oil test data, and proposed that this method has advantages in the division of reservoir productivity and delineation of payzone range. However, porosity spectrum can only enable qualitative evaluation of reservoir effectiveness but not quantitative evaluation of the pore structure of reservoir. Capillary pressure curve is the most direct and effective option for quantitative evaluation of pore structure. Xiao et al.

[27] correlated the porosity spectrum with the capillary pressure curve for classified reservoirs and then plotted the capillary pressure curve from the FMI porosity spectrum. Xiao et al. proposed that compared with

T2 spectrum of NMR logging, FMI is conducive to constructing capillary pressure curve and evaluating reservoir pore structure for three reasons. (1) FMI measures the shallow detection depth, and the FMI porosity spectrum is not affected by fluid properties in the pore. (2) FMI is applicable for reservoirs with fracture width more than 2 mm. (3) the FMI porosity spectrum has a higher vertical resolution than the NMR

T2 spectrum, and thus a higher accuracy of pore structure evaluation

[27]. Nevertheless, FMI still faces problems as follows. First, it requires a classification of reservoirs based on the actual capillary pressure curve shape, but the classification of highly heterogeneous reservoirs is difficult. Second, the plotted capillary pressure curve is not universal, since it is only applicable to the reservoir types classified by the actual capillary pressure curve. Third, the porosity component calculated by calibrating the conductivity or resistivity measured by microelectrode with Archie's equation is dimensionless, and there is no theoretical basis for converting dimensionless porosity component into pore size component with length dimension, i.e. the porosity component is not equivalent to the pore size component, so it is theoretically impossible to convert porosity into capillary pressure through calibration. The previous studies attempted to establish porosity spectrum and capillary pressure curve to expand the application of FMI in characterization of physical properties and pore structure, but did not propose the approach or idea of using FMI to characterize reservoir permeability and permeability spectrum

[28-29].