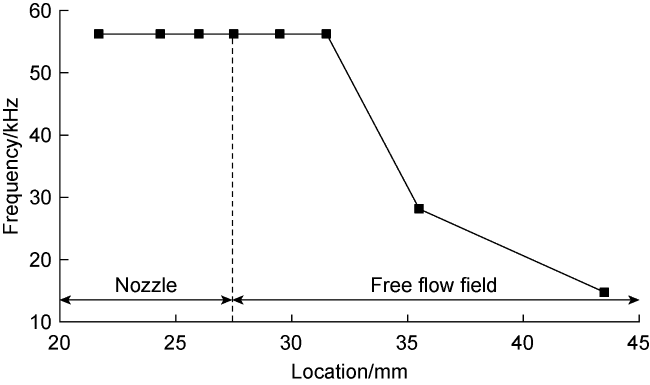

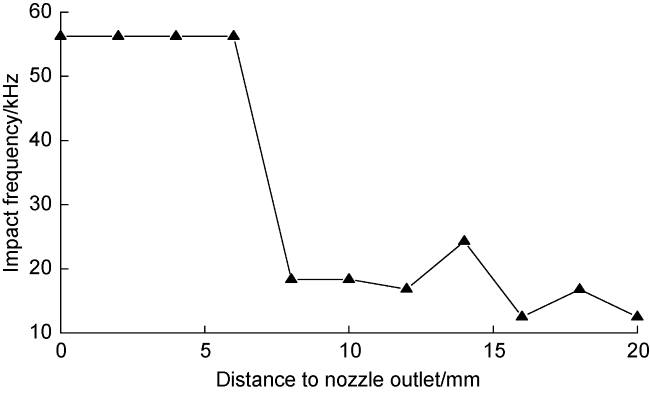

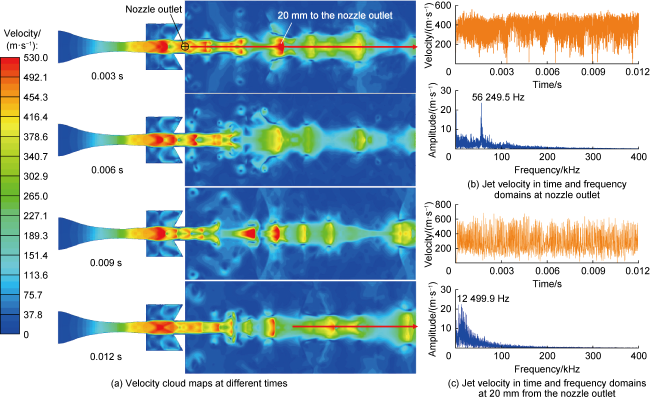

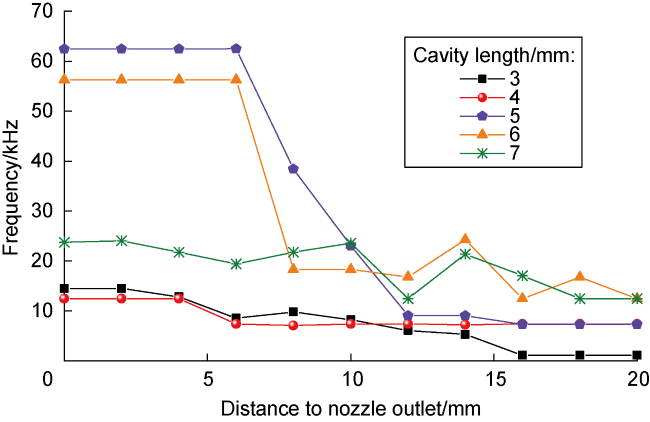

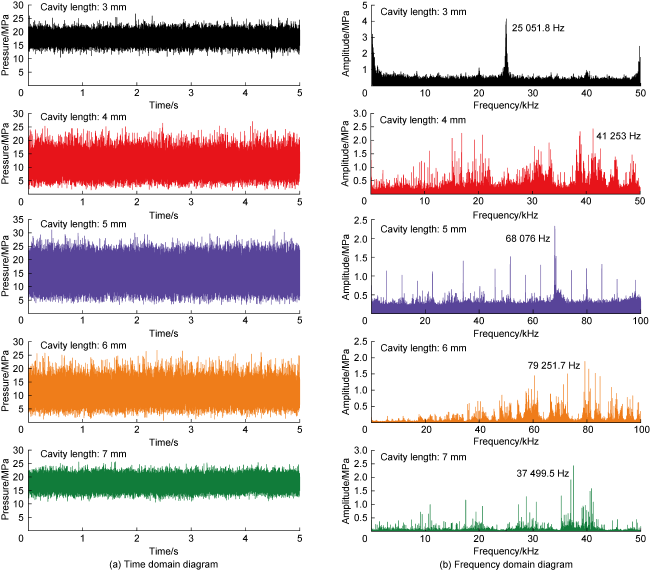

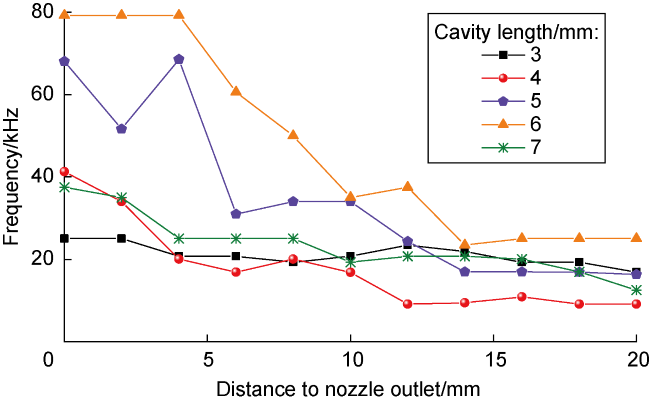

As shown in

Fig. 8 and

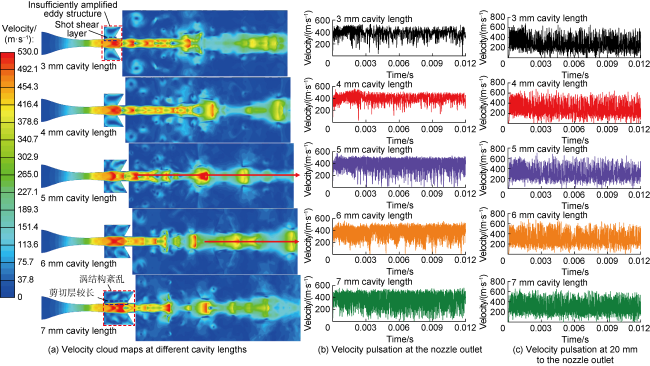

Fig. 9, when the cavity length is 6 mm, the frequency of the self-excited oscillation pulsed SC-CO

2 jet inside the nozzle is 79 251.7 Hz, and the amplitude is 1.89 MPa. After ejected from the nozzle, the jet impact frequency decreased to 25 004.4 Hz with the increase of the axial distance to nozzle outlet. When the cavity length is 3 mm, the jet impact frequency at the nozzle outlet is 25 051.8 Hz, and the amplitude is 4.14 MPa. After ejected, the impact frequency tends to oscillate and decrease to 16 898.2 Hz with the development of the jet. When the cavity length is 4, 5, 7 mm, there is a poor feedback effect of the eddy structure, which makes the pulsation of the initial shock wave at the nozzle outlet longer, so that the impact frequency of the self-excited oscillation pulsed SC-CO

2 jet at the nozzle outlet reduced to 41 253, 68 076, 37 499.5 Hz, and the amplitude is 2.43, 2.32, 2.47 MPa, respectively. With the development of the jet, the impact frequency reduced to 9098.1, 16 290, 12 496.4 Hz, respectively. The self-excited oscillating pulsed SC-CO

2 jet exhibits the rock breaking characteristics of high frequency and micro-amplitude under the nozzle structure. With the increase of the cavity length, the jet frequency at the nozzle outlet first increases and then decreases. With the increase of the distance to the nuzzle outlet, the jet frequency decreases as a whole. These conclusions are consistent with numerical simulations, which verify the variation law of the impact frequency of self-excited oscillation pulsed SC-CO

2 jets. In field applications, the resonant frequency of coal under different excitation frequency conditions is not consistent, so the coal breaking effect can be enhanced by adjusting the length of the oscillating cavity to change the jet frequency. For example, if the inherent frequency of coal is 35 Hz

[8], when using a self-excited oscillating nozzle with an oscillating cavity of 6 mm to break the coal at 0 mm from the nozzle, the impact frequency will be 2264.3 times the inherent frequency of the coal. To achieve the resonant coal-breaking effect, the length of the oscillating cavity can be adjusted to 5 mm, so that the impact frequency is 1945 times the inherent frequency of the coal.