a—wellbore inclination, (°);

a31, a32, a33, a34, a35, a36—flexibility matrix coefficients of transversely isotropic medium, dimensionless;

b1, b2, b3—modulus at direction i, j, k respectively, dimensionless;

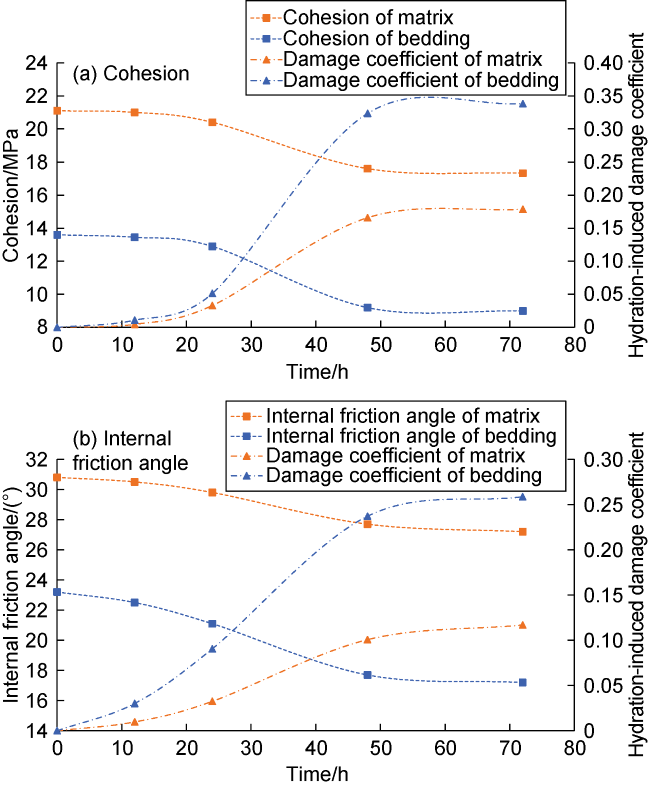

cbo, cb(t)—cohesion of original shale bedding and that of shale bedding during hydration, MPa;

cmo, cm(t)—cohesion of original matrix and that of matrix during hydration, MPa;

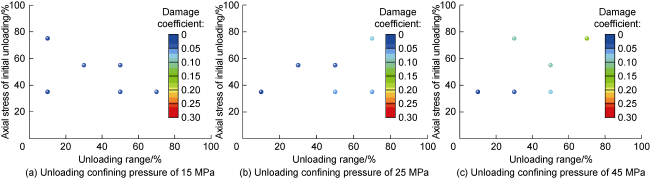

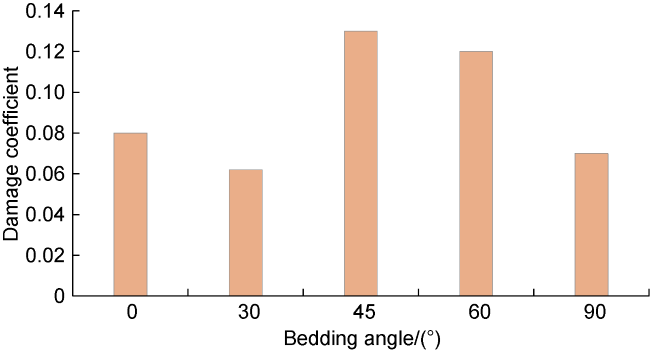

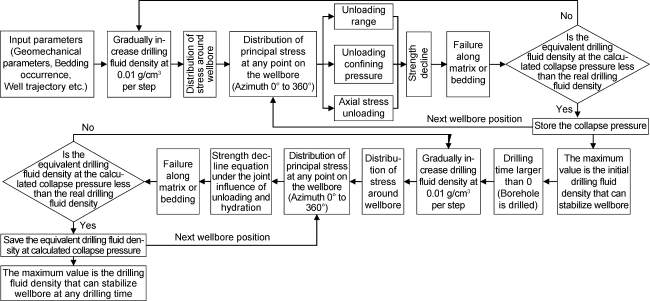

D—damage coefficient, dimensionless;

Du—damage coefficient caused by unloading, dimensionless;

Dh(t), Dhmc(t), Dhmi(t)—hydration damage coefficients of shale, matrix cohesion and matrix internal friction angle at time t, dimensionless;

Dhbc(t), Dhbi(t)—hydration damage coefficients of bedding cohesion and bedding internal friction angle at time, dimensionless;

i, j, k—unit vectors in the directions of the Cartesian axis;

n—normal vector of bedding;

N—vector along the maximum principal stress on wellbore;

pw—liquid column pressure, MPa;

Re—the real part of a complex number;

x, y, z—rectangular coordinate system, m;

z1, z2, z3—complex variables;

α—Biot coefficient, dimensionless;

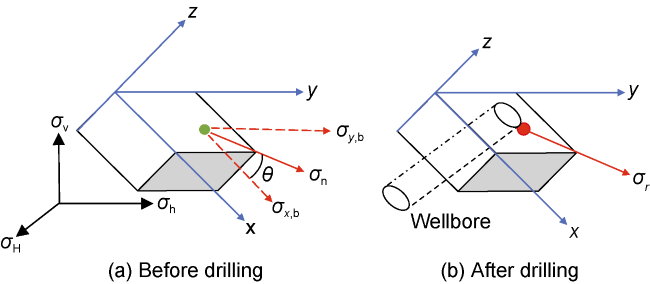

βw—included angle of maximum principal stress and bedding, (°);

βuw—included angle of principal stress and unloading direction, (°);

βo—included angle of failed matrix plane and maximum principal stress, (°);

γ—included angle of maximum principal stress and axial direction, (°);

δ—permeability coefficient of wellbore, dimensionless;

θ—circumferential angle, (°);

λ1, λ2, λ3—ratio of characteristic roots, dimensionless;

μ1, μ2, μ3—characteristic roots of characteristic equation corresponded to strain coordination equation, dimensionless;

ν—Poisson’s ratio, dimensionless;

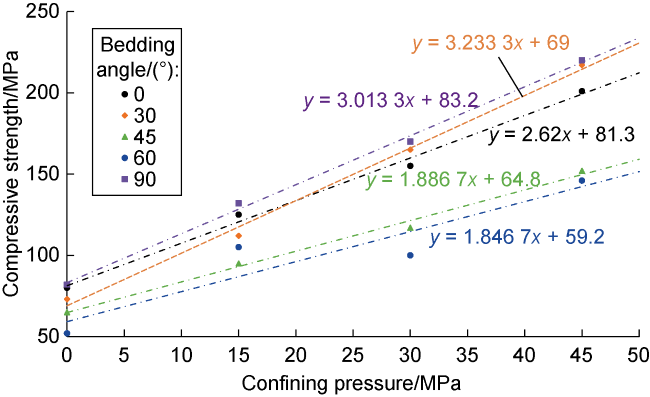

σ1, σ3—maximum and minimum principal stresses, MPa;

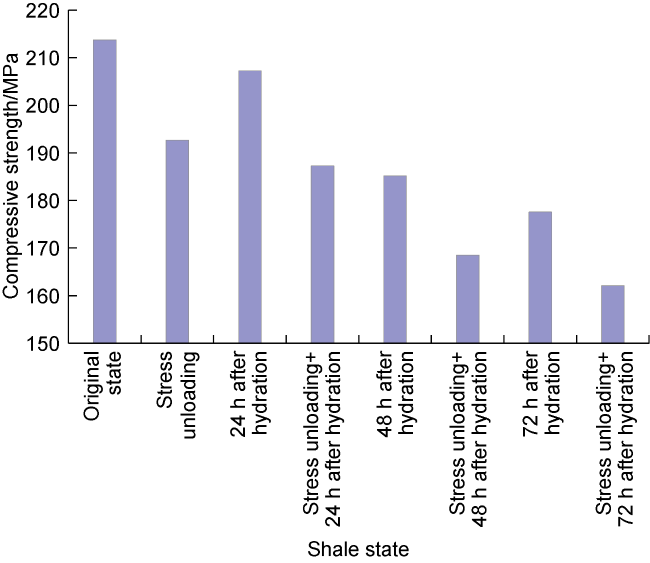

σc—compressive strength of original shale, MPa;

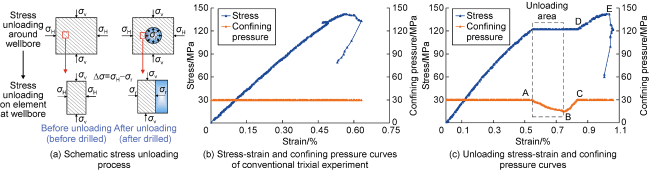

σcu—compressive strength after stress unloading, MPa;

σi, σj, σk—three principal stresses on the wellbore, MPa;

σn—component of in-situ stress along unloading direction, MPa;

σv, σH, σh—vertical, maximum and minimum horizontal principal stress, MPa;

σr, σz, σθ—radial stress, stress along z-axis, circumferential stress at cylindrical coordinate system, MPa;

τrz, τθz, τrθ—shear stress tangent to planes rz, θz, rz at cylindrical coordinate system, MPa;

σx,b, σy,b, σz,b—stress around wellbore in laminated formation along x-axis, y-axis, z-axis, MPa;

τxy,b, τyz,b, τxz,b—shear stress around wellbore tangent to planes xy, yz, xz in laminated formation, MPa;

σx,o, σy,o, σz,o—stress around wellbore at in-situ stress along x-axis, y-axis, z-axis, MPa;

τxy,o, τyz,o, τxz,o—shear stress around wellbore tangent to planes xy, yz, xz at in-situ stress, MPa;

σx,h, σy,h—boundary stresses along x-axis, y-axis of the wellbore after drilling, MPa;

τxy,h, τyz,h, τxz,h—boundary stresses tangent to planes xy, yz, xz along the wellbore after drilling, MPa;

Δσ—unloading stress variation, MPa;

ϕ1, ϕ2, ϕ3—analytic functions of transversely isotropic equation;

φbo, φb(t)—internal friction angle of original bedding plane and that of the bedding plane after hydration, (°);

φmo, φm(t)—internal friction angle of original shale matrix and that of the shale matrix after hydration, (°).