Introduction

1. Overview of coal rock gas

Table 1. Comparison of coal rock gas and coalbed methane |

| Gas type | Geological characteristics | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gas source | Distribution | Burial depth/m | Reservoir physical properties | Cleats/ fractures | Migration mode | |||||||||||||||||

| Coal rock gas | Self-source or external source | Gentle areas or structural belts within basin | 2 000- 4 000 | Porosity 0.1%- 16.0%; permeability (0.001-15.000)× 10−3 μm2 | Fractures with aperture greater than 5 μm: 10-19 fractures/9 cm2; fractures with aperture less than 5 μm: 94-308 fractures/9 cm2 | Primary migration (diffusion flow), secondary migration (Darcy flow) | ||||||||||||||||

| Coalbed methane | Self-source | Structural belts or uplifted areas at basin margins | Few hundreds to 1 500 | Porosity 0.1%-8.0%; permeability (0.001- 0.500)×10−3 μm2 | Cleats/fractures developed in shallow coals | Primary migration (diffusion flow) | ||||||||||||||||

| Gas type | Geological characteristics | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Accumulation mechanism | Caprock conditions | Trap types | Preservation conditions | Reservoir temperature/°C | Reservoir pressure/ MPa | |||||||||||||||||

| Coal rock gas | Free, absorption (buoyancy, van der Waals force) | Caprock lithology has significant impact, including mudstone, limestone and tight sandstone | Stratigraphic-lithological trap, micro-amplitude structures locally | Trap and pressure sealing; deep burial, weak hydrodynamics | 65-135 | 22-33 | ||||||||||||||||

| Coalbed methane | Absorption (van der Waals force) | Caprock lithology has minimal impact | Stratigraphic-lithological trap, micro- amplitude structures, hydrodynamics | Pressure sealing, shallow burial, strong hydrodynamics, influenced by atmospheric fresh water infiltration | About 40 | 4-8 | ||||||||||||||||

| Gas type | Geological characteristics | Development characteristics | ||||||||||||||||||||

| In-situ gas density/ (kg•m-3) | Gas saturation | Gas content/ (m3•t-1) | Free gas content | Gas-logging peak value | Carbon isotopes | Development technology | Production characteristics | Predicted ultimate recovery/ 104 m3 | ||||||||||||||

| Coal rock gas | 130- 210 | High, up to 98.6% | Up to 34.0 m3/t, average 21.8 m3/t | Up to 45%, average 24.48% | Gas-logging total hydrocarbon peak greater than 90%, or even up to 100% | δ13C1: −37.6‰ to −16.0‰, δ13C2: −21.7‰ to −14.3‰ | Vertical well, horizontal well or high-angle horizontal well volume fracturing | Well produces gas immediately after it is opened, showing a bimodal production profile [6] | 4 000- 6 000 | |||||||||||||

| Coalbed methane | About 60 | Relatively large change | 8-12 | Low | Relatively low | Relatively light δ13C1: −70.50‰ to −36.19‰ [14] | Long production period, showing a monomodal production profile [6] | Generally less than 2 500 | ||||||||||||||

2. Geological setting and coal rock characteristics

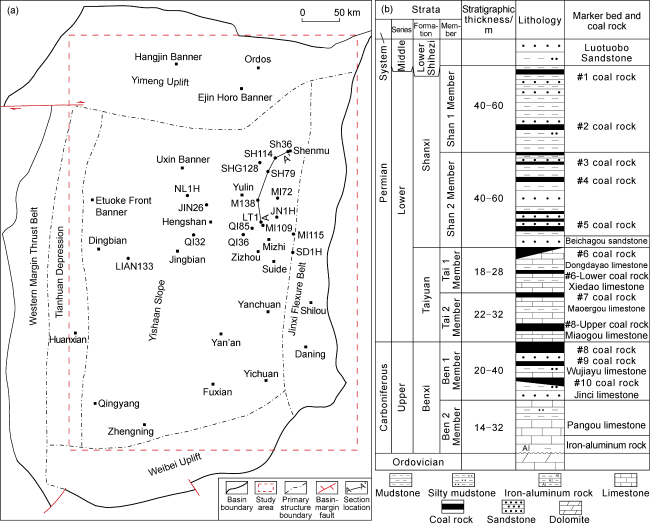

2.1. Geological setting

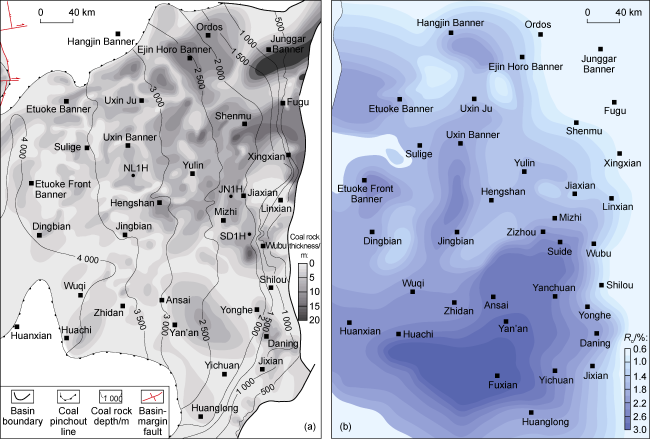

Fig. 2. Coal rock thickness map (a) and Ro contour map of the Benxi Formation (b) in the Ordos Basin (Fig. a is modified from Reference [19]). |

2.2. Coal rock distribution and coal quality of the Benxi Formation

2.2.1. Coal rock deposition and distribution

2.2.2. Coal quality

3. Conditions for coal rock gas accumulation in the Benxi Formation

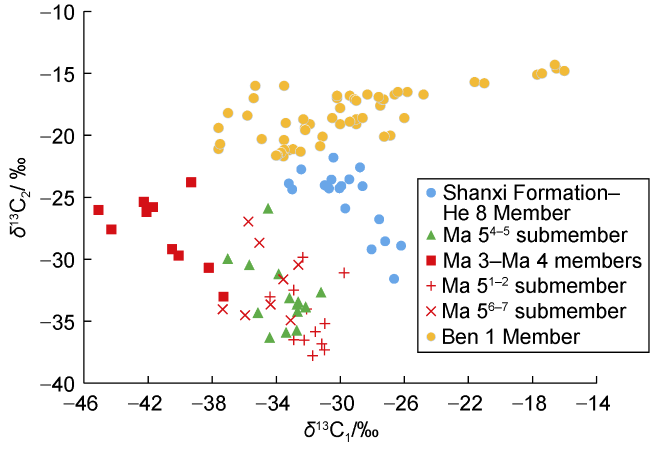

3.1. High gas generation capacity of high-rank coal rocks

Fig. 3. Carbon isotopic composition of natural gas in typical formations in the Ordos Basin. |

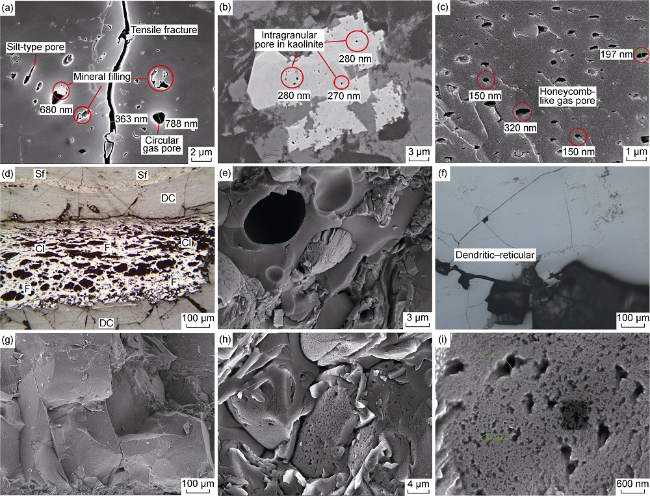

3.2. Development of coal rock reservoirs

3.2.1. Storage space types of coal rock reservoirs

Fig. 4. Microscopic characteristics of coal rock reservoirs in the Benxi Formation of Ordos Basin. (a) Well QI85, 2629.23 m, tensile fracture with aperture of 363 nm, gas pores with diameter of 680-788 nm, SEM; (b) Well QI85, 2 631.40 m, intragranular pores in kaolinite, with diameter of 270-280 nm, SEM; (c) Well QI85, 2 629.34 m, gas pores, with diameters ranging from tens to hundreds of nanometers, SEM; (d) Well QI85, 2 629.15 m, clay-filled fusinite pores, cleats and microfractures in desmocollinite; (e) Well MI115, 2 901.40 m, clay-filled fusinite cell cavity pores, SEM; (f) Well JIN26, 3 101.24 m, dendritic cleats/fractures; (g) Well JIN26, 3 103.40 m, coal vitrinite in dominance, microfractures, SEM; (h) Well JIN26, 3 103.40 m, microfractures and gas pores, SEM; (i) Well JIN26, 3 103.40 m, locally magnified, gas pores, with diameters ranging from nanometers to hundreds of nanometers, SEM. Cl—clay; DC—desmocollinite; F—fusinite; Sf—semi-fusinite. |

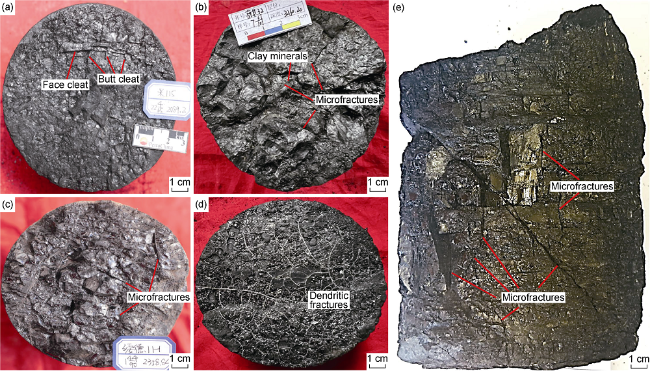

Fig. 5. Core photographs of the Benxi Formation in the Ordos Basin. (a) Well MI115, 2 089.20 m, bright coal in dominance, with face cleats and butt cleats; (b) Well QI32, 3 260.20 m, bright coal in dominance, arrows indicating deformed clay minerals between bright coal blocks, with unfilled microfractures; (c) Well SD1H, 2 358.84 m, bright coal, with face cleats and butt cleats, as well as some fractures filled with calcite; (d) Well QI32, 3 265.36 m, bright coal in dominance, with dendritic and reticular fractures, filled with minerals; (e) Well LIAN133, 3 864.20 m, bright coal in dominance, with cleats, microfractures dominated by shear fractures due to tectonic stress, as well as vertical fractures. |

Fig. 6. Electrical imaging log of #8 coal rock in Well SHG128 (arrows indicate effective open fractures). |

3.2.2. Physical properties of coal rock reservoirs

Table 2. Physical properties of coal rock reservoirs in Benxi Formation |

| SN. | Well | Depth/m | Porosity/% | Permeability/ 10−3 μm2 | Sample type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MI115 | 2 087.78 | 0.540 | 0.001 | Plug |

| 2 | MI115 | 2 090.32 | 1.610 | 0.001 | Plug |

| 3 | MI115 | 2 105.32 | 3.570 | 0.155 | Plug |

| 4 | MI172 | 2 425.20 | 10.670 | 3.470 | Plug |

| 5 | MI172 | 2 425.45 | 4.770 | 0.802 | Plug |

| 6 | MI172 | 2 427.64 | 8.480 | 0.673 | Plug |

| 7 | MI172 | 2 427.89 | 7.700 | 1.537 | Plug |

| 8 | MI172 | 2 428.39 | 5.630 | 0.743 | Plug |

| 9 | MI172 | 2 428.65 | 6.610 | 1.162 | Plug |

| 10 | MI172 | 2 428.99 | 1.200 | 0.001 | Plug |

| 11 | MI172 | 2 429.29 | 8.470 | 2.096 | Plug |

| 12 | JIN26 | 3 101.33 | 5.333 | 14.600 | Plug |

| 13 | JIN26 | 3 102.46 | 6.551 | 12.000 | Plug |

| 14 | JIN26 | 3 103.48 | 4.992 | 10.900 | Plug |

| 15 | MI109 | 2 373.93 | 5.947 | 0.048 | Block |

| 16 | MI109 | 2 374.80 | 3.708 | 0.005 | Block |

| 17 | MI109 | 2 375.80 | 1.937 | 0.020 | Block |

| 18 | MI109 | 2 376.30 | 2.491 | 0.158 | Block |

| 19 | QI36 | 2 805.34 | 6.370 | 0.942 | Block |

| 20 | QI36 | 2 806.78 | 9.116 | 0.096 | Block |

| 21 | QI36 | 2 807.62 | 7.929 | 0.338 | Block |

| 22 | QI36 | 2 808.57 | 5.136 | 1.192 | Block |

| Average | 5.398 | 2.315 | |||

Table 3. Statistics of microscopic cleats in the coal rocks |

| Sample | Microscopic cleat density/[cleats·(9 cm2)−1] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A-Type | B-Type | C-Type | D-Type | Total | |

| JIN26-2 | 3 | 10 | 62 | 160 | 235 |

| JIN26-5 | 2 | 10 | 20 | 74 | 106 |

| JIN26-8 | 7 | 12 | 52 | 92 | 163 |

| QI85-1 | 3 | 12 | 48 | 260 | 323 |

| QI85-5 | 2 | 14 | 32 | 220 | 268 |

| QI85-8 | 2 | 8 | 30 | 214 | 254 |

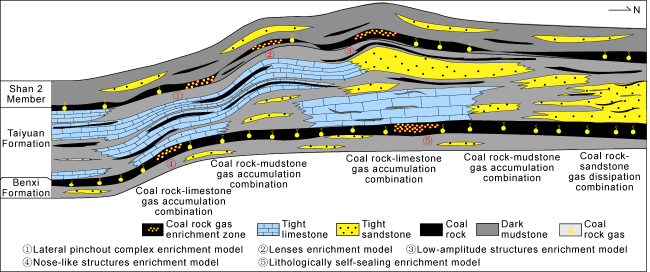

3.3. Coal rock gas accumulation and dissipation combinations

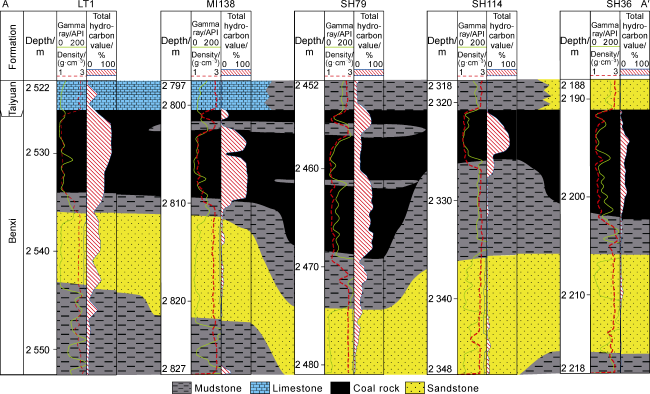

Fig. 7. Sections of the Benxi Formation coal rocks and the overlying and underlying strata of in the Ordos Basin (section location in |

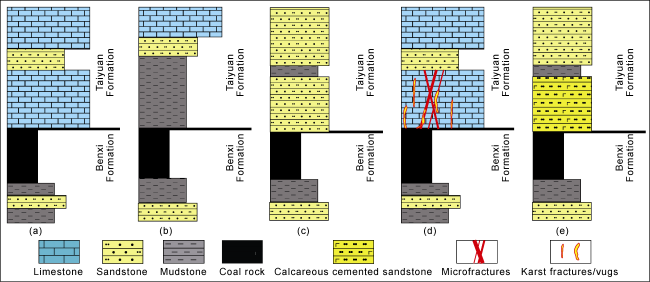

Fig. 8. Coal rock gas accumulation and dissipation combinations of the Benxi Formation in the Ordos Basin. (a) Coal rock-limestone gas accumulation combination; (b) Coal rock-mudstone gas accumulation combination; (c) Coal rock-sandstone gas dissipation combination; (d) Coal rock-limestone gas dissipation combination; (e) Coal rock-tight sandstone gas accumulation combination. |

3.4. Coal rock gas accumulation and enrichment models

3.4.1. Coal rock gas accumulation

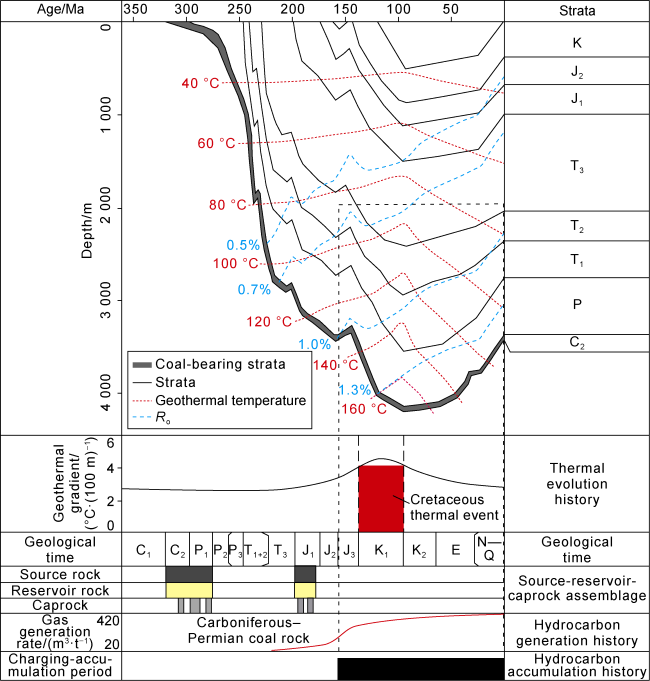

Fig. 9. Coal rock gas accumulation process in the Ordos Basin. |

3.4.2. Coal rock gas enrichment models

Fig. 10. Types and models of coal rock gas enrichment in the Ordos Basin. |

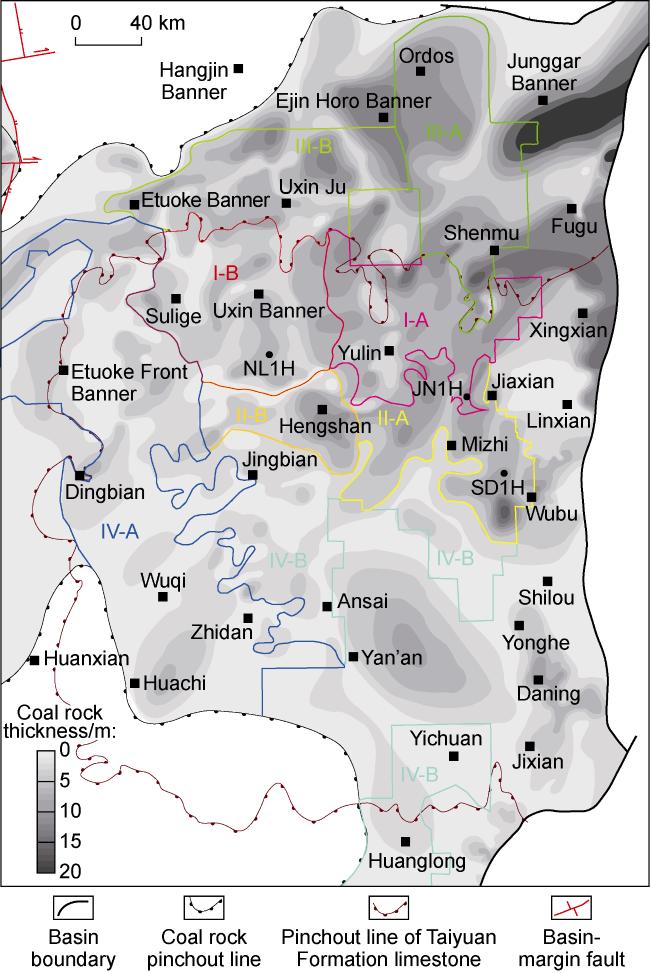

4. Comprehensive evaluation and target selection

4.1. Resource assessment and exploration potential

Fig. 11. Comprehensive evaluation of coal rock gas in Benxi Formation of the Ordos Basin. |

Table 4. Division and geological resources of coal rock gas evaluation plays in the Benxi Formation of the Ordos Basin |

| Play | Play code | Ro/% | Coal rank | Depth/m | Area/km2 | Weighted coal rock thickness/m | Geological resources/108 m3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yulin | I-A | 1.2-1.6 | Medium | 2 000-3 000 | 7 322.4 | 8.02 | 15 010.4 |

| Wushen Banner | I-B | 1.6-2.4 | Medium to high | 3 000-3 800 | 9 386.0 | 4.85 | 13 574.7 |

| Mizhi-Suide | II-A | 1.6-2.4 | Medium to high | 2 000-3 000 | 6 841.1 | 6.87 | 14 014.8 |

| Hengshan | II-B | 1.8-2.4 | Medium to high | 3 000-3 500 | 3 522.1 | 5.19 | 5 451.0 |

| Ordos | III-A | 0.8-1.2 | Medium to high | 1 000-2 500 | 9 811.9 | 8.57 | 11 940.5 |

| Wushen Ju | III-B | 1.0-2.0 | Low | 2 500-3 700 | 8 361.7 | 6.83 | 16 219.3 |

| Dingbian-Huachi-Zhidan | IV-A | 1.4-2.8 | Medium to high | 3 500-4 000 | 27 800.0 | 4.00 | 28 422.7 |

| Ansai-Qingjian-Huanglong | IV-B | 1.8-3.0 | Medium to high | 1 500-4 000 | 18 300.0 | 4.00 | 18 709.9 |

| Total/Average | 91 345.0 | 6.04 | 123 343.3 |

4.2. Play evaluation and risk target determination

Table 5. Comprehensive evaluation of coal rock gas in the Benxi Formation of the Ordos Basin |

| Play code | Play | Depositional environment | Caprock thickness/m | Thickness of coal seam/m | Combination type | Peak value of total hydrocarbon/% | Well deployed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I-A | Yulin | Delta front | 2-13 | 4-14 | Coal rock-mudstone gas accumulation combination | 91 | JN1H |

| I-B | Wushen Banner | 2-19 | 80 | NL1H | |||

| II-A | Mizhi-Suide | Barrier- lagoon in delta front | 30-50 | 4-16 | Coal rock-limestone gas accumulation combination | 100 | SD1H |

| II-B | Hengshan | 2-10 | 80 | ||||

| III-A | Ordos | Delta plain | 8-26 | 4-20 | Coal rock-sandstone gas accumulation and dissipation combination | 30 | |

| III-B | Wushen Ju | 2-12 | 48 | ||||

| IV-A | Dingiban-Huachi- Zhidan | Shallow marine- lagoon in delta front | 8-15 | 2-6 | Coal rock-mudstone gas accumulation combination | 40 | |

| IV-B | Ansai-Qingjian- Huanglong | 2-6 | Coal rock-limestone gas accumulation combination | 58 |