As early as the 1990s, Elbel et al.

[4] proved for the first time through experiments that initial fracturing of oil and gas wells could reverse the principal stress direction by 90°. Subsequently, Wright et al.

[5], based on the elastic mechanics of porous media, explained the internal mechanism of stress field changes induced by pore pressure reduction from the perspective of reservoir compaction and fracture slip. Gupta et al.

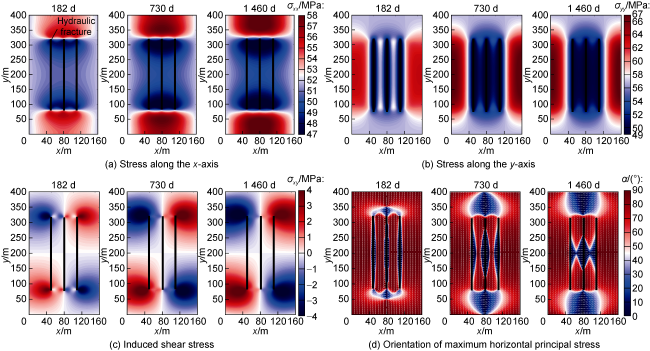

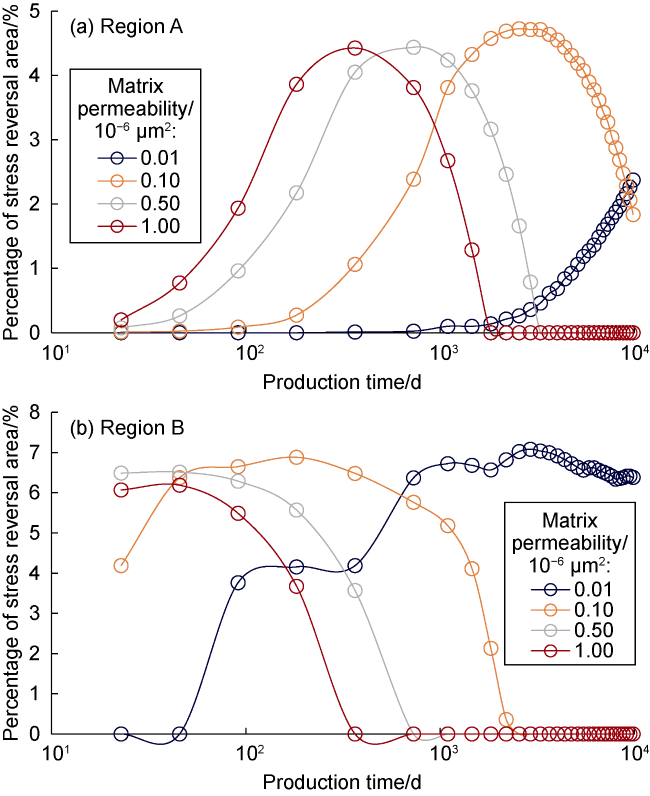

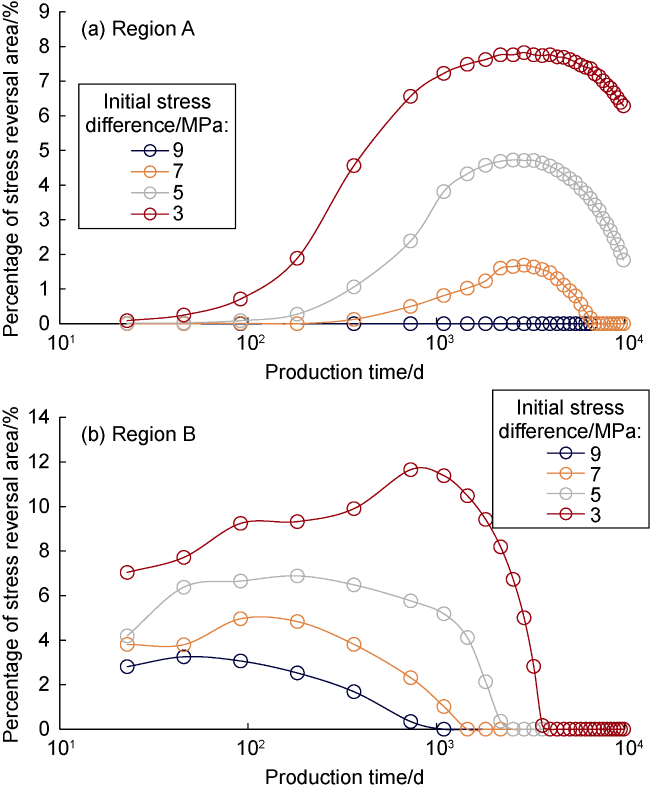

[6] believed that there is a relationship between the change of stress field and reservoir development, and the smaller the initial horizontal principal stress difference of the reservoir, the more conducive to the in-situ stress reversal. Roussel et al.

[7] verified the stress reversal phenomenon and concluded that the principal stress direction around the infill well was reversed by 90°. Safari et al.

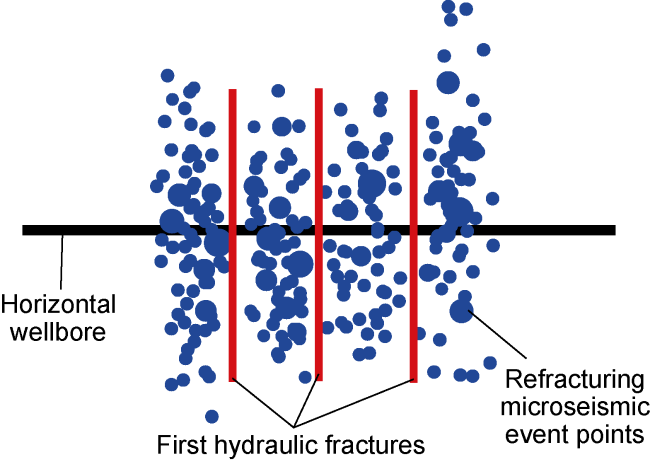

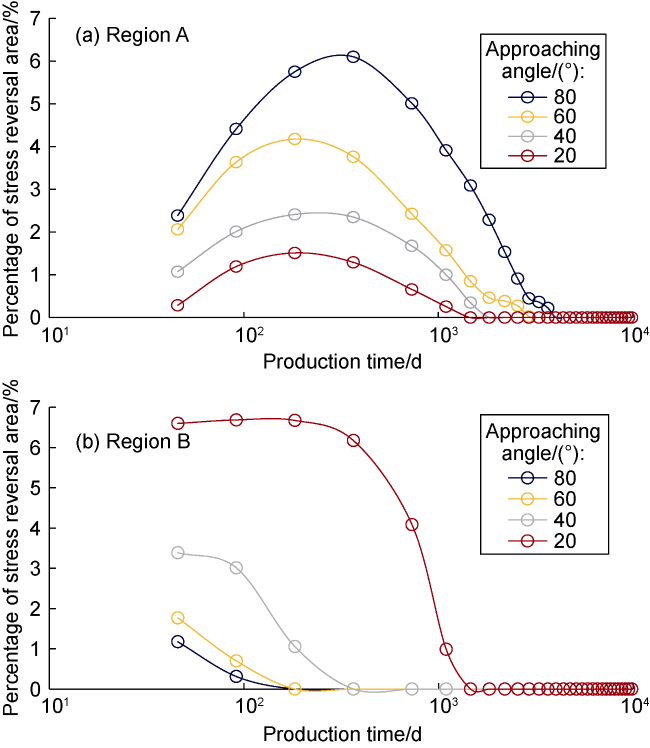

[8-9] found that due to the stress reorientation of horizontal wells, hydraulic fractures may bend or straight fractures may form during the fracturing process of infill wells, mainly depending on the reversal of the principal stress. However, they did not provide a method for optimizing the fracturing timing of infill wells. Sangnimnuan et al.

[10] established a coupled seepage-geomechanics model based on an embedded discrete fracture model, which was used to characterize the stress field induced by pressure depletion in unconventional reservoirs with complex geometric fractures. They obtained conclusions similar to those of Gupta. Kumar et al.

[11] established a three-dimensional fully coupled model to simulate the stress redirection behavior caused by production, and obtained the fracture propagation trajectory of infill wells affected by stress redirection. Sangnimnuan et al.

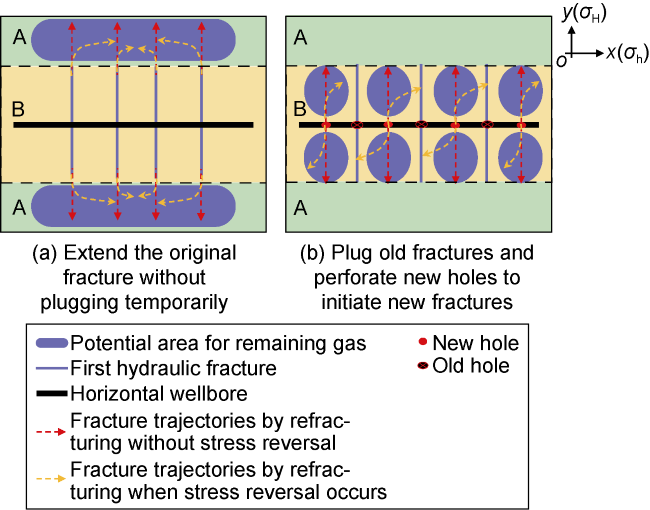

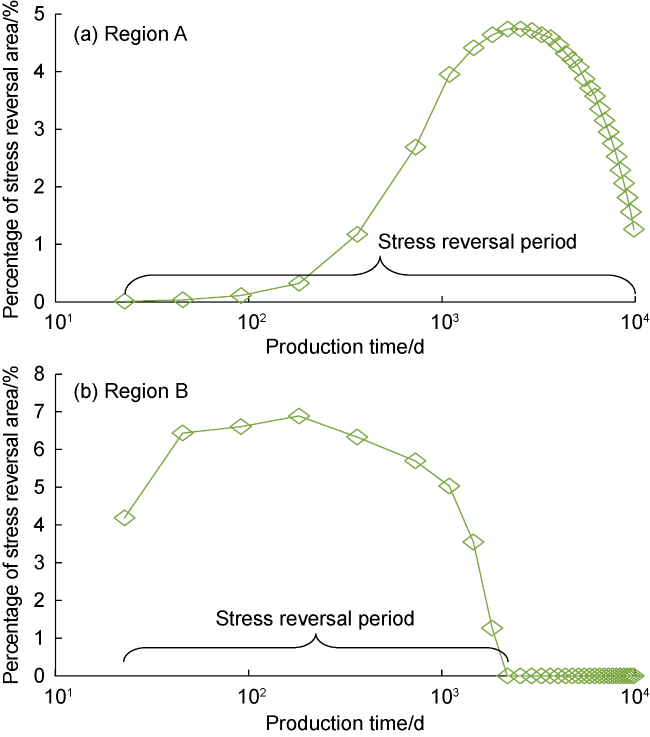

[12] found that stress reversal has a significant impact on the selection of refracturing methods by studying the pressure and stress distribution after the pressure depletion of fractured reservoirs. Ibáñez et al.

[13] developed an integrated multidisciplinary workflow that can screen suitable candidate wells and evaluate the feasibility of refracturing candidate wells using geomechanical modeling. Zhu et al. combined Eclipse and ABAQUS to propose a numerical simulation method for four-dimensional in-situ stress evolution of multiple physical fields in tight sandstone reservoirs during injection and production development

[14-15]. Xia et al.

[16] established a stress field evolution prediction model, revealing the law of in-situ stress evolution induced by intra and inter layer mining in vertically heterogeneous shale reservoirs. Guo et al. also pointed out that the changes in production-induced stress field are very important for the design of refracturing, but did not provide the optimal timing for refracturing from the perspective of stress evolution

[17-18].