Introduction

1. Global distribution of basement reservoir accumulation

Fig. 1 Number of basement reservoirs in the world (modified from Reference [1]; the lithology of weathering basement is unknown). |

Table 1 Basic characteristics of global basement reservoirs |

| No. | Country | Basin | Basin type | Oil/gas reservoir | Onshore/ Offshore | Horizon | Reservoir rock type | Recoverable oil reserves/ 108 t | Recoverable gas reserves/ 108 m3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Vietnam | Cuu Long | Back-arc basin | Bach Ho | Offshore | J | Granite, diorite | 2.15 | 511.40 |

| 2 | Venezuela | Maracaibo | Foreland basin | La Paz | Onshore | Pz | Crystalline basement, metamorphic rock | 0.49 | 246.19 |

| 3 | Indonesia | South Sumatra | Back-arc basin | Suban | Onshore | K2 | Crystalline basement, metamorphic rock | 811.56 | |

| 4 | Vietnam | Cuu Long | Back-arc basin | Rang Dong | Offshore | J | Granite, diorite | 0.34 | 76.46 |

| 5 | China | Bohai Bay | Back-arc basin | BZ19-6 | Offshore | Ar | Granite, gneiss | 0.14 | 450.24 |

| 6 | Libya | Sirte | Rift basin | Amal | Onshore | Ar | Volcanic breccia | 0.28 | 36.81 |

| 7 | India | Mumbai | Rift basin | Mumbai High | Offshore | Ar | Metamorphic rock, igneous rock | 0.22 | 56.63 |

| 8 | Venezuela | Maracaibo | Foreland basin | Mara | Onshore | AnPz-Pz | Granite, metamorphic rock | 0.16 | 48.49 |

| 9 | Vietnam | Cuu Long | Back-arc basin | Su Tu Vang | Offshore | J | Granite, diorite | 0.17 | 28.32 |

| 10 | Russia | West Siberia | Back-arc basin | Novoportovskoye | Onshore | C | Weathered basement * | 224.55 | |

| 11 | Brazil | Sergipe | Rift basin | Carmopolis | Onshore | Pz2 | Metamorphic rock | 0.14 | 6.14 |

| 12 | China | Bohai Bay | Back-arc basin | Xinglongtai | Onshore | Ar | Gneiss | 0.09 | 6.51 |

| 13 | Yemen | Sayun-Masila | Rift basin | Tawila | Onshore | An | Granite | 0.09 | 5.66 |

| 14 | Hungary | Pannonian | Back-arc basin | Ulles | Onshore | Pz | Dolomite, schist | 98.82 | |

| 15 | China | Bohai Bay | Back-arc basin | Jinganbao | Onshore | Ar | Metamorphic rock | 0.06 | 5.23 |

| 16 | China | Bohai Bay | Back-arc basin | Chengdao | Offshore | Ar | Gneiss | 0.05 | 2.83 |

| 17 | Libya | Sirte | Rift basin | Rakb | Onshore | Ar | Weathered basement * | 0.05 | 3.82 |

| 18 | Norway | Horda Platform | Rift basin | Rolvsnes | Offshore | Ar | Granite, gneiss | 0.04 | 12.18 |

| 19 | China | Bohai Bay | Back-arc basin | Huanxiling | Onshore | Ar | Metamorphic rock | 0.03 | 7.55 |

| 20 | Thailand | Phitsanulok | Rift basin | Sirikit | Onshore | AnK-K | Metamorphic rock | 0.03 | 2.12 |

2. Basic characteristics of basement reservoirs

2.1. Strong reservoir heterogeneity and early reservoir-forming time

Table 2 Basic characteristics of basement reservoirs |

| Rock type | Lithology | Storage space type | Reservoir characteristics and distribution patterns | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metamorphic rocks | Mainly dynamic metamorphic glutenite, gneiss, schist, granitic gneiss, and mixed rocks | Porous-fractured and fractured, with dual porosity, low porosity and ultra-low permeability | The storage spaces of reservoirs in weathering zones are primarily composed of pores, followed by fractures, with the fracture-pore combination in dominance. The storage spaces of interior reservoirs are mainly characterized by pore-fracture type and fracture type. Rocks with predominantly light-colored minerals are brittle and more prone to fragmentation, forming reservoirs. Folding and faulting actions control the development of fracture zones. | The Archaean metamorphic rock buried-hill reservoirs in the Bozhong Depression, the Carboniferous-Permian metamorphic rock reservoirs in the Central Uplift Zone of the Songliao Basin, the metamorphic rock buried-hill reservoirs in the Liaohe Basin, and the metamorphic rock reservoirs in the Altyn Tagh piedmont in the Qaidam Basin. |

| Granite | Mainly granodiorite and monzodiorite | Fractured-porous and fractured, with the storage spaces dominated by intergranular pores, feldspar and amphibole dissolution pores, microfractures, joints, and structural fractures | Medium-acid granites with a higher felsic content are more favorable for the development of reservoirs. The reservoirs are vertically zoned, and exhibit weathering crust type and interior type. The former is dominated by weathering process, with the storage spaces primarily composed of pores and fractures-pores. The degree of pore/fracture development and the intensity of weathering are positively correlated. The latter is dominated by tectonic process, with the storage spaces mainly composed of fractures and cavities, showing a low matrix porosity. | The granite buried-hill reservoirs in the Bach Ho Oilfield of Cuu Long Basin in Vietnam, and the granite buried-hill reservoirs in the Penglai 9-1 Oilfield, the Dongping area of the Qaidam Basin, and the Huizhou Sag of the Pearl River Mouth Basin in China. |

| Medium-basic volcanic rocks | Mainly two series: subalkaline and alkaline. The former is dominated by andesite, basaltic andesite, dacite, and rhyolite, while the latter is mainly represented by basaltic trachyandesite. | Dominantly fractured-cavity reservoirs, with dissolution cavities being the primary feature (the main dissolved minerals are feldspar and amphibole), followed by fractures (particularly structural and dissolution fractures) | Rocks such as volcanic breccias and rhyolite of explosive and effusive facies exhibit the optimal reservoirs properties | Reservoirs in the Carboniferous of the Junggar Basin, the Permian of the Sichuan Basin, and the Jurassic of the Huizhou Sag in the Pearl River Mouth Basin. |

Fig. 2 Distribution of basement lithology in the northern margin of the Qaidam Basin. |

Fig. 3 Variation of porosity with depth for basement and sandstone reservoirs in the Qaidam Basin. |

2.2. Allochthonous hydrocarbon source and multiple types of source-reservoir assemblages

Fig. 4 Types of source rock-basement assemblages. |

Fig. 5 Distribution of basement reservoirs in sedimentary basins. |

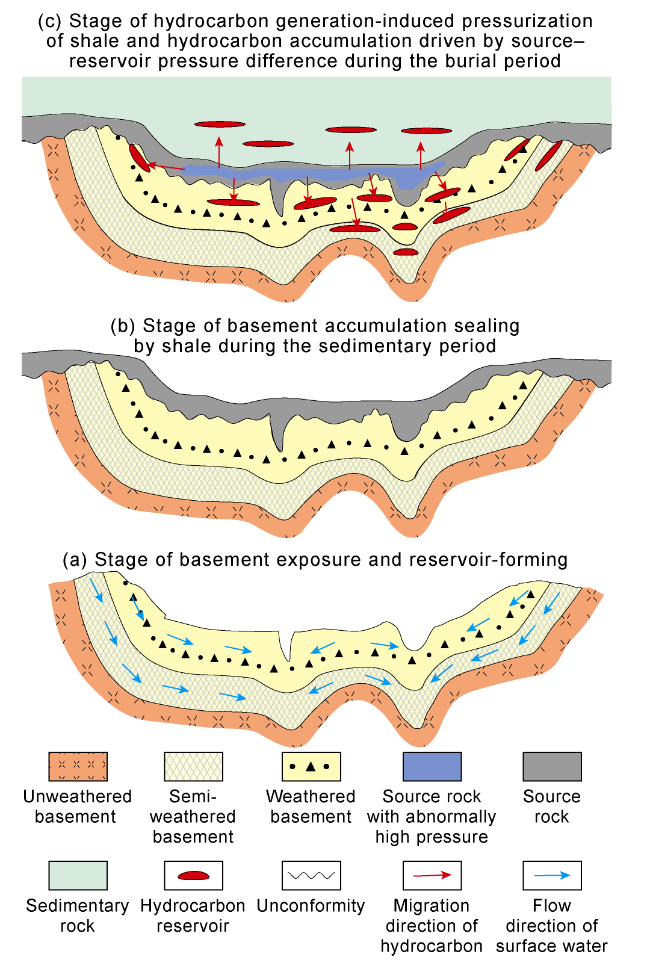

2.3. Hydrocarbon accumulation by pumping effect under the driving of source-reservoir pressure difference

Fig. 6 Depth-pressure relationship of basement and sandstone reservoirs in the Bohai Bay Basin. |

Fig. 7 Model of hydrocarbon accumulation by pumping effect in basement reservoirs under the driving of source-reservoir pressure difference. |

Table 3 Maximum depth of oil and gas migration in fractured basement reservoirs under normal pressure |

| Source rock burial | Maximum depth of vertical downward migration of oil droplet at different pressure coefficients/m | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| depth/m | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.8 |

| 3 000 | 600 | 900 | 1 200 | 1 500 | 1 800 | 2 400 |

| 3 500 | 700 | 1 050 | 1 400 | 1 750 | 2 100 | 2 800 |

| 4 000 | 800 | 1 200 | 1 600 | 2 000 | 2 400 | 3 200 |

| 4 500 | 900 | 1 350 | 1 800 | 2 250 | 2 700 | 3 600 |

| 5 000 | 1 000 | 1 500 | 2 000 | 2 500 | 3 000 | 4 000 |