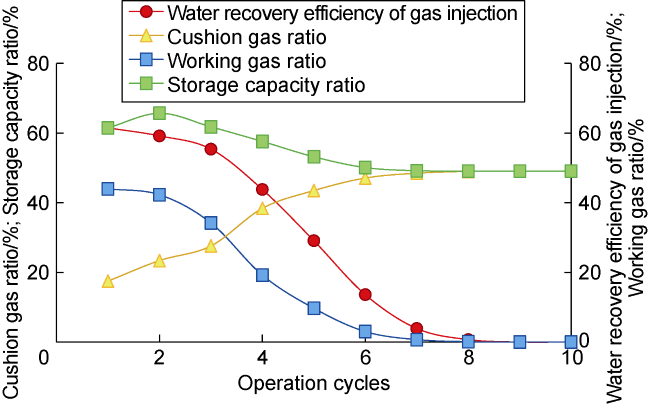

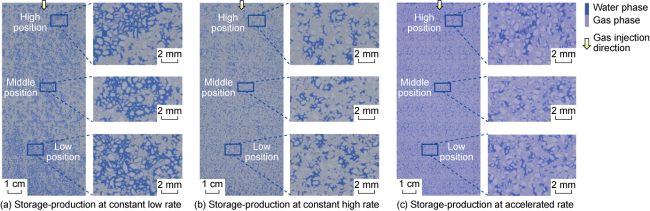

By comparing Scheme 2 and Scheme 3, it can be known that the gas-liquid interface shows a stable migration state. The rates in both schemes can be considered as stable displacement rates. By tracing the evolution of the gas-liquid interface through image processing techniques, the recovery efficiency of gas injection can be calculated at different times. The migration rate of a point on the gas-liquid interface at a certain time is defined as the ratio of the vertical distance between the point and the injection end to the experimental time. The average of the migration rates at the front and the ends of the gas-liquid interface is defined as the average migration rate of the interface. The relationship between the average migration rate or recovery efficiency of gas injection and the experimental time was plotted (

Fig. 4). Based on the average migration rate of the interface, the method of Grattoni et al.

[13] was used to calculate the gravity number and Bond number at different times, which were then compared 1, so as to determine the main controlling mechanical mechanism. An increase of the Bond number to 1 indicates that the fluid flow changes from capillary pressure-dominated to gravity-dominated. A decrease of the gravity number to 1 indicates that the fluid flow changes from gravity-dominated to viscous force-dominated. In this study, the final recovery efficiencies under schemes 2 and 3 are relatively high, reaching 74.7% and 78.6% respectively. The curves of both schemes show a pattern of four stages: unchanged in the initial stage, slow growth in the early stage, rapid growth in the middle stage, and stable in the late stage. There are no values in the initial stage because of the strong compressibility of gas, which causes gas to accumulate and compress at the top until reaching a threshold pressure before starting to flow. The range where each mechanical mechanism plays a leading role is strongly correlated with changes in the average migration rate of the interface and the recovery efficiency of gas injection. The position where the main controlling mechanical mechanism changes occurs at the turning point of the curve, indicating that competition and changes between mechanical mechanisms essentially control the morphology of the gas-liquid interface and the recovery efficiency of gas injection during displacement

[14]. In both schemes, the morphology of the gas-liquid interface was dominated by capillary pressure in the early stage, and by gravity in the middle stage when the recovery efficiency increased by 66 percent points in Scheme 2 and by 62 percent points in Scheme 3. After gas breakthrough, the recovery efficiency curve in Scheme 2 is nearly flat, while the recovery efficiency curve in Scheme 3 levels up slightly and further increases by 2 percent points. This indicates that after the displacement by gas injection became stable and gas broke through, the process was dominated by viscous force. The higher the gas injection rate, the stronger the viscous force, which is more conducive to the improvement of recovery efficiency after gas breakthrough. Although schemes 2 and 3 adopt very different gas injection rates, they are similar in zonal division and size of mechanical mechanisms, resulting in almost identical final displacement characteristics. For a stable gravity displacement process, the displacement characteristics before gas breakthrough are dominated by capillary pressure and gravity, but less influenced by viscous force; after gas breakthrough, the displacement process is dominated by viscous force. This result is consistent with the finding in long-core displacement experiments in Reference [

15].