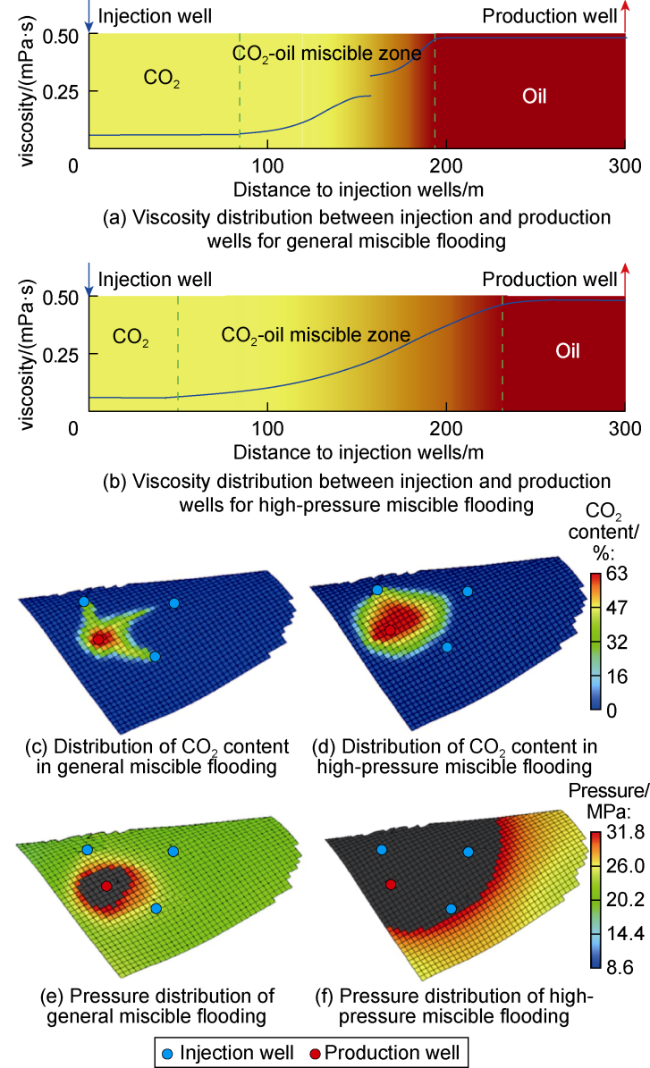

CO

2 flooding front reaches the production well along the high permeability channel in the late stage of CO

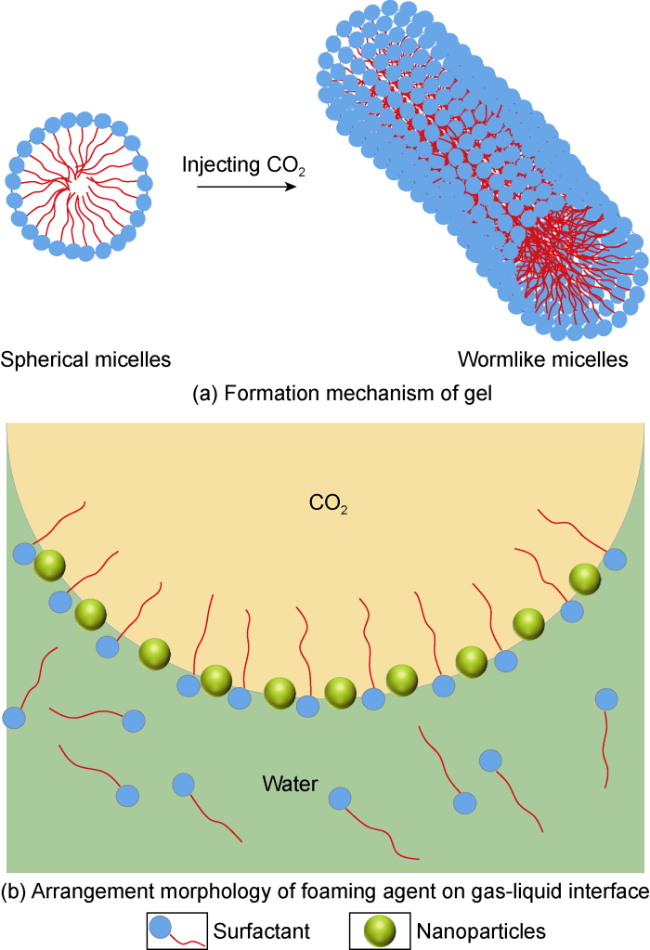

2 flooding, causing an increase in gas-oil ratio and gas breakthrough in some production wells. Aiming at the gas channeling control in fractures and large pores, an alkyl isopropanol amine surfactant was synthesized by introducing a tertiary amine response group, and salt additives were optimized to construct a CO

2-responsive gel system. Alkyl isopropanol amine surfactant is protonated under acid conditions, and the aggregate morphologically changes from spherical micelle to wormlike micelle under the induction of salt additives, thereby crosslinking each other to form a three-dimensional network gel system (

Fig. 9a)

[29]. The viscosity of CO

2-responsive gel system is less than 3 mPa·s, with good injectivity before injection into formation. But it responds to viscosity increase in gas channels with high gas saturation after injection into the formation. The viscosity can reach over 400 mPa·s, with high-strength plugging properties under the conditions of a temperature of 120 °C and salinity of 10×10

4 mg/L. The plugging rate for high permeability rock cores with permeability of 2 000× 10

−3 μm

2 can reach over 80%. In reservoir matrix with high oil saturation, micelles have a solubilization effect on crude oil, resulting in a decrease in system viscosity and minimal reservoir damage. For CO

2 channeling caused by interlayer and intralayer heterogeneity in the matrix, CO

2-philic carbonyl group is introduced into the hydrophobic tail chain of alkanes with carbon number of 12-16, and the sulfate radical with strong hydration is introduced into the head group to form a temperature resistant and salt resistant CO

2 foaming agent. Modified nanoparticles are added to further improve the elasticity of the CO

2 foam liquid film (

Fig. 9b). Under the temperature of 120 °C and the salinity of 10×10

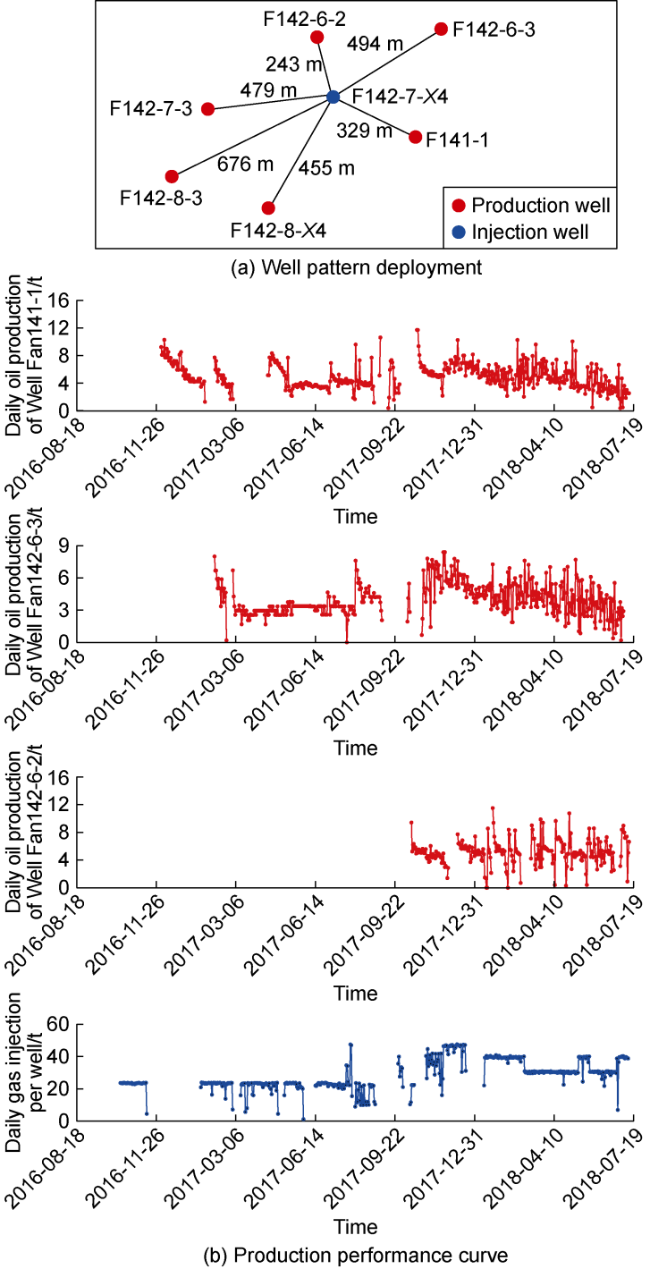

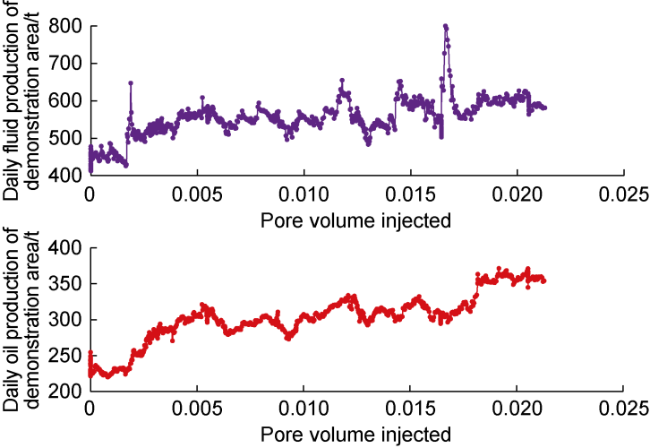

4 mg/L, the system exhibits excellent foaming properties, with a resistance factor of up to 60 and a good plugging effect. This technology has been successfully applied in Gao 89-Fan 142 demonstration area of Shengli Oilfield, with a 100% effective rate. CO

2 content in the production well Fan 142-10-2 decreased from 92.5% to 10.1% after the treatment, and the daily oil production increased from 1.1 t to 4.4 t, with an effective period of over 0.5 years.