Currently, data mining and artificial intelligence are increasingly applied in various industrial fields and have achieved remarkable results, presenting opportunities for the digital transformation of the traditional petroleum industry

[10⇓-12]. Their application in petroleum field at present stage includes geological model parameterization

[13-14], geoscientific modeling

[15-16], fluid property prediction

[17], well production prediction

[18-19], sweet-spot detection

[20], and shale gas recovery calculation

[21-22]. Deep learning

[23], renowned for its efficacy in modeling nonlinear relationships and its capabilities in automated learning and abstract feature extraction from input data, facilitates more complex mapping and characterization. This offers innovative approaches for constructing surrogate models aimed at predicting reservoir performance for automatic history matching

[24-25] and production optimization

[26⇓⇓⇓-30]. Zhu et al.

[31] constructed a Bayesian deep Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) to quantify geological uncertainty. Tripathy et al.

[32] developed a single-phase flow forward simulation surrogate model, while Laloy et al.

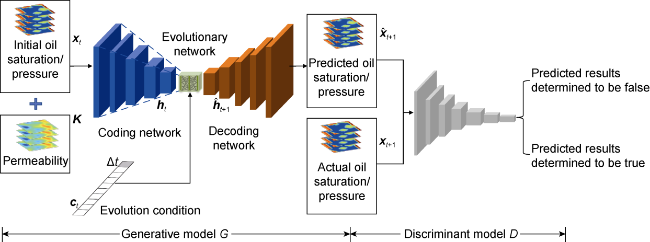

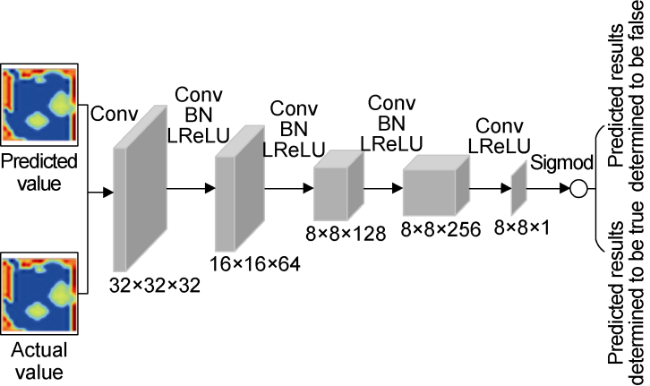

[33] built the same model using Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN), in which the high-dimensional projections are determined by training two adversarial neural networks. Wang et al.

[34] proposed a neural network for predicting single-phase flow in two-dimensional porous media under theoretical guidance. Zhong et al.

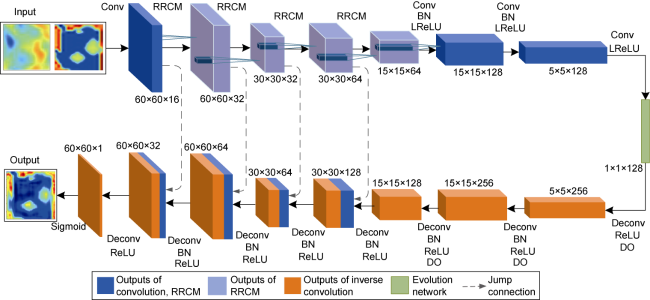

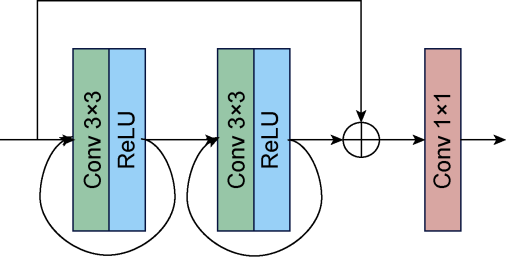

[35-36] used GAN to construct a surrogate model to simulate reservoir pressure and fluid saturation. Ma et al.

[37-38] combined a CNN and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) to predict the production data, which reduced the additional computation caused by images. Jin et al.

[39] proposed the embedded control (E2C) framework to predict well response and dynamic evolution of 2D heterogeneous reservoirs in different well control conditions without considering geological uncertainty. Wei et al.

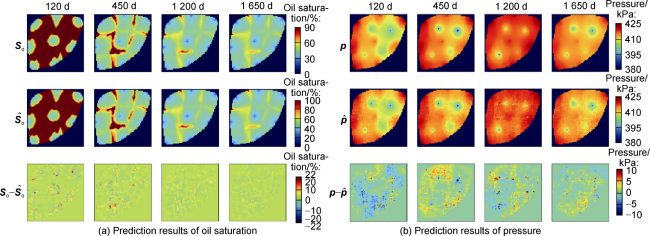

[40] used the ConvLSTM model to predict oil saturation and bottom-hole pressure distribution at different production moments using actual oilfield data. Zhang et al.

[41] employed vector-type features and high-dimensional spatial-type parameters as CNN input to predict pressure and oil saturation. Huang et al.

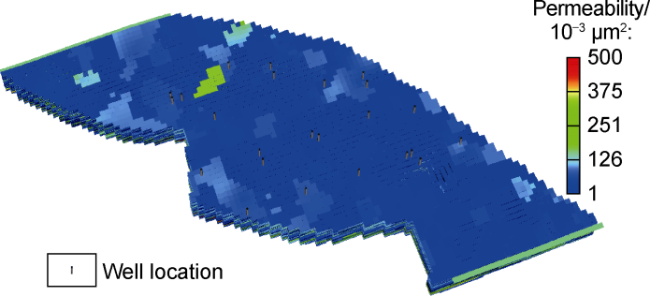

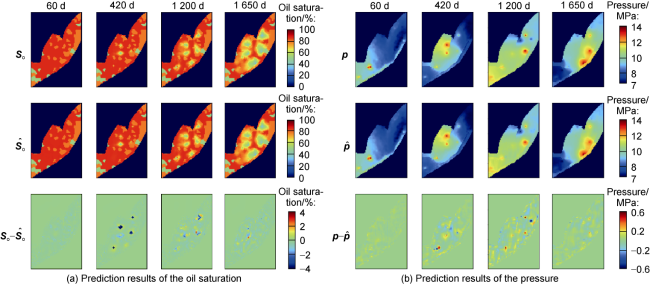

[42] constructed a deep-learning surrogate model for the rapid 3D simulation of actual reservoirs. Although this model takes into account different well control conditions, it does not fully consider the uncertainty of production time.