Introduction

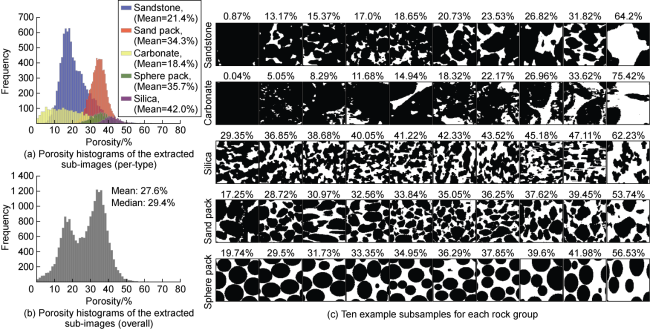

1. Dataset development

Fig. 1. Porosity histograms and example subsamples for each rock type (in Fig. (c), percentage represents porosity, and white and black zones represent pore and solid pixels). |

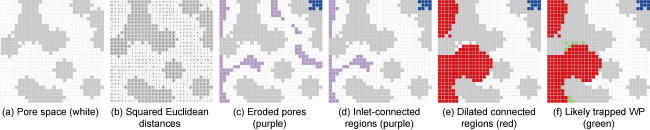

Fig. 2. Distance-based PMS implementation (grey represents rock pixels, and blue represents the pore region isolated from the inlet). |

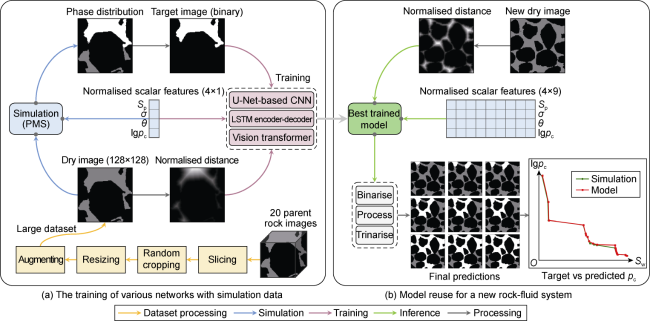

2. Model development and analysis

Fig. 3. Network training based on PMS simulation results and application of the model to a new rock-fluid system (black, gray and white represent solid, WP and NWP, respectively). |

2.1. U-Net-based CNN

2.1.1. Architecture and training

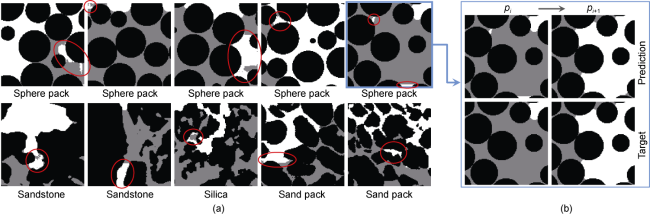

2.1.2. Testing

Fig. 4. The worst-case prediction mistakes made by Y-Net. |

2.2. Convolutional LSTM encoder-decoder

2.2.1. Architecture and training

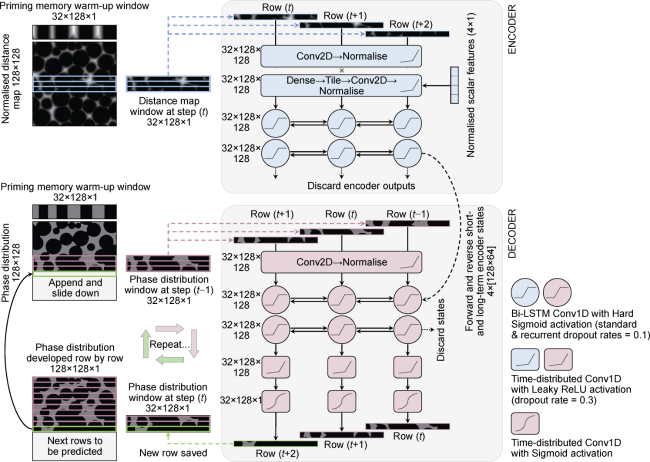

Fig. 5. Architecture of convolutional LSTM encoder-decoder (the size of the window for autoregressive prediction is 32). For visual clarity, a window size of 3 is assumed here. |

2.2.2. Testing

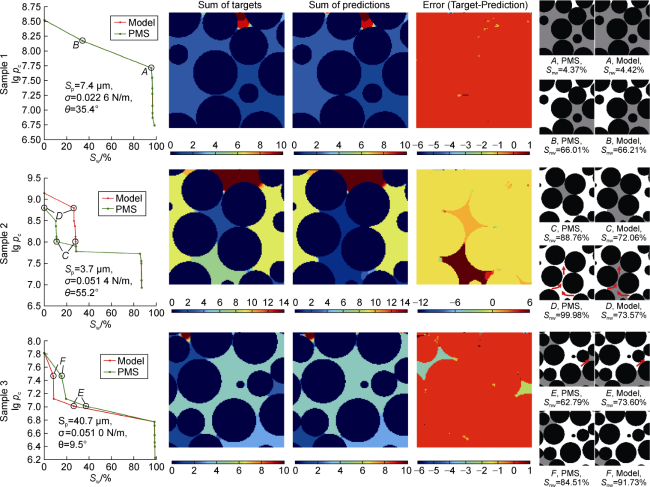

Fig. 6. Ψ-Net performance on three testing samples from the sphere pack (warm colours represent earlier stages of displacement, and cool colours represent later ones.) |

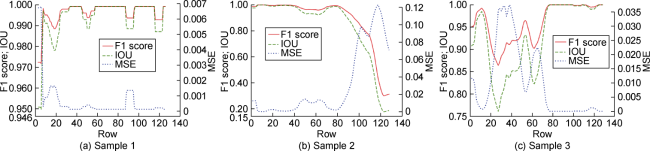

Fig. 7. Moving averages of performance metrics for all rows of the three samples from |

2.3. Vision transformer with higher-dimensional data

2.3.1. Architecture and training

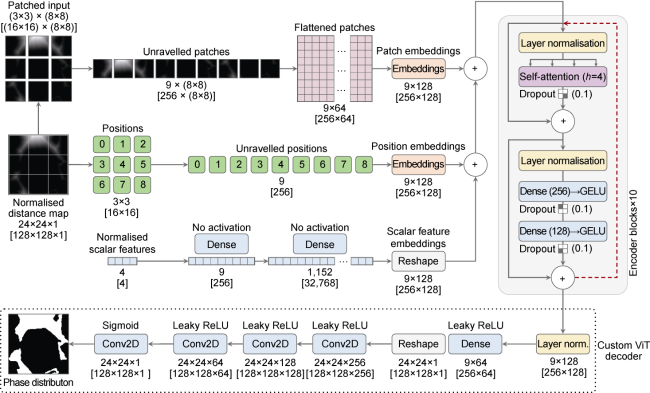

Fig. 8. ViT architecture. An input image size of 24×24×1 is assumed for enhanced readability. True sizes are shown in brackets. |

2.3.2. Testing

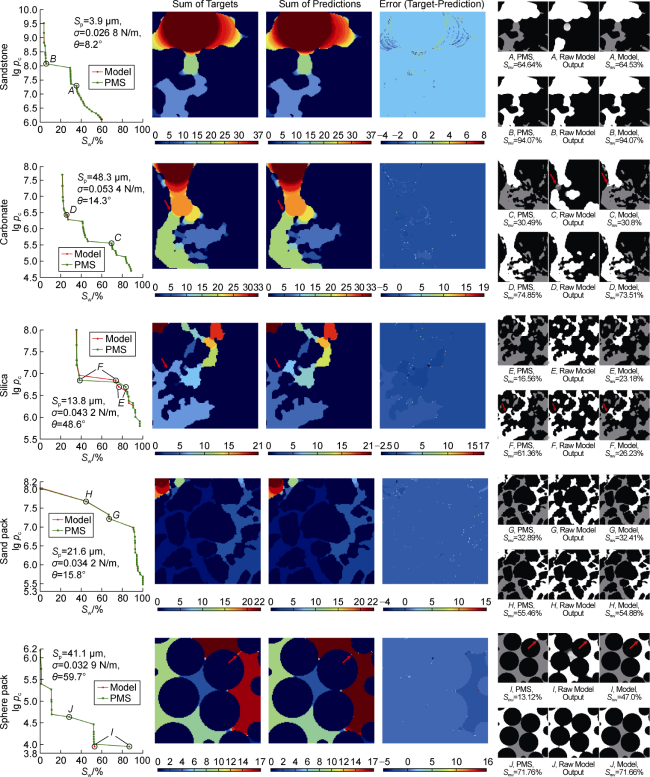

Fig. 9. HD-ViT targets and predictions for five testing samples (warm colours represent earlier stages of displacement, and cool colours represent later ones). |

3. Model verification and extension to 3D

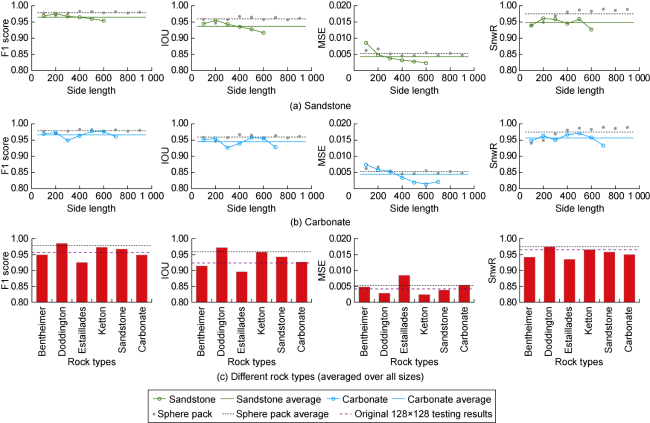

3.1. Performance vs rock type and image size

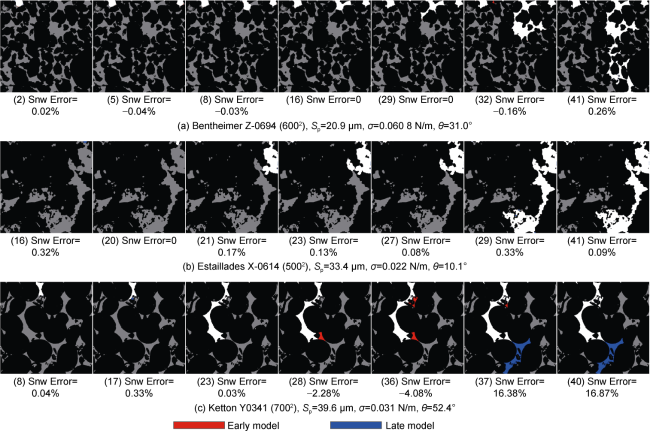

Fig. 10. HD-ViT predictions for three new larger images (the numbers in bracket represent the series number of pressure step). |

Fig. 11. HD-ViT performance vs. rock type and image size. |

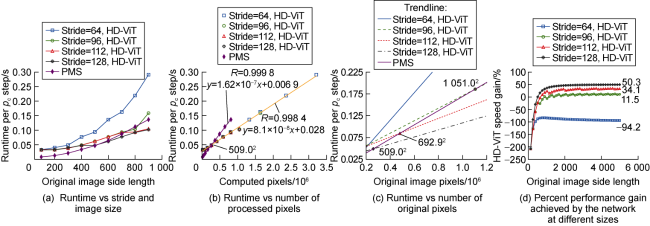

3.2. Model runtimes compared to simulations

Fig. 12. Runtime comparison between HD-ViT and PMS. |

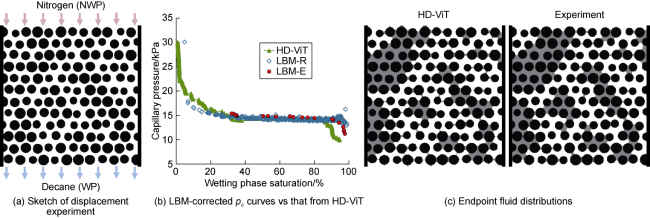

3.3. Experimental verification

Fig. 13. Comparison between HD-ViT, experiments, and LBM simulations in a 2D micromodel. |

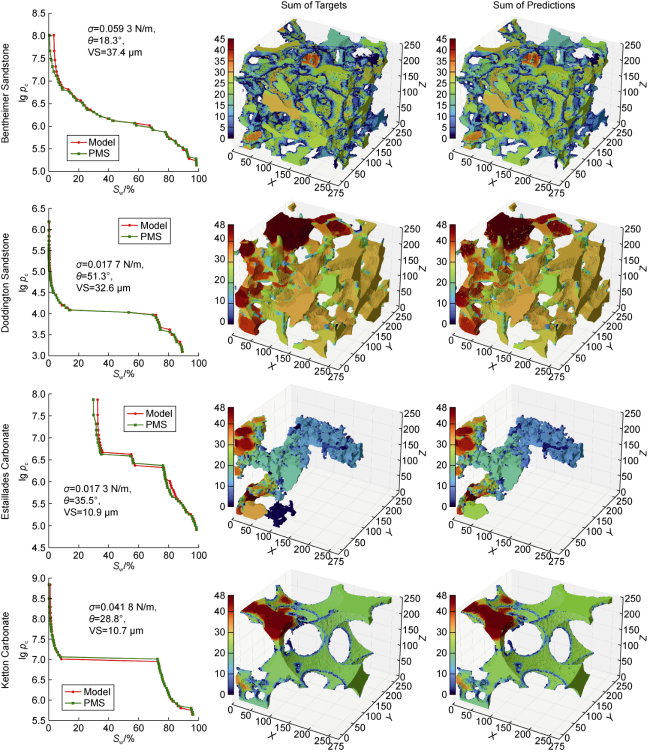

3.4. Extension to 3D

Fig. 14. pc curves and fluid distributions of four testing rocks by PMS simulation and HD-ViViT prediction (warm colours represent earlier stages of displacement, and cool colours represent later ones). VS stands for Voxel Size. |