For shale oil, there are three mainstream methods for evaluating its retained hydrocarbon content: pyrolysis method, stepwise extraction method, and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) method. The pyrolysis method can be divided into two sub-types: conventional pyrolysis and stepwise pyrolysis

[40-41]. The former uses the free hydrocarbon content (

S1) to reflect the volume of retained hydrocarbons in the shale strata, but the

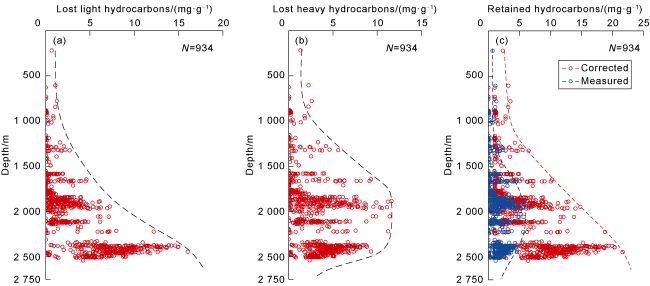

S1 tested usually suffers light hydrocarbon loss and heavy hydrocarbon loss. By combining hydrocarbon generation kinetics with rock pyrolysis parameters of shale samples before and after extraction,

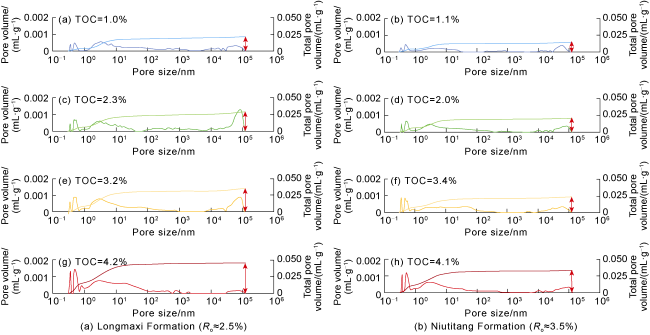

S1 can be restored for light hydrocarbons and corrected for heavy hydrocarbons, thereby obtaining the retained hydrocarbon content in shale. The stepwise pyrolysis method determines the retained hydrocarbon content through quantitative evaluation on shale oil in different occurrence states in shale strata, under proper heating conditions, considering that such shale oils in different occurrence states are distinct in molecular thermal volatilization capacity, and that temperature ranges correspond to non-polar free compounds, polar free compounds, heavy hydrocarbons, and adsorbed substances (e.g. resin and asphaltene). The stepwise extraction method obtains the contents of hydrocarbons in different occurrence states by collecting extracts with solvents of different volumes or polarities, considering that the molecules with different compositions and polarities are selective in occurrence space and state

[42]. The NMR method directly calculates the contents of shale oil in different occurrence states by distinguishing free oil and adsorbed oil depending on the differences of free oil, adsorbed oil, and kerogen in relaxation time on 2D NMR spectra

[43]. In addition, molecular dynamics model, free hydrocarbon difference method, swelling method, material balance method, and pore oil saturation method can also be used to evaluate the contents of shale oil in different occurrence states

[44].